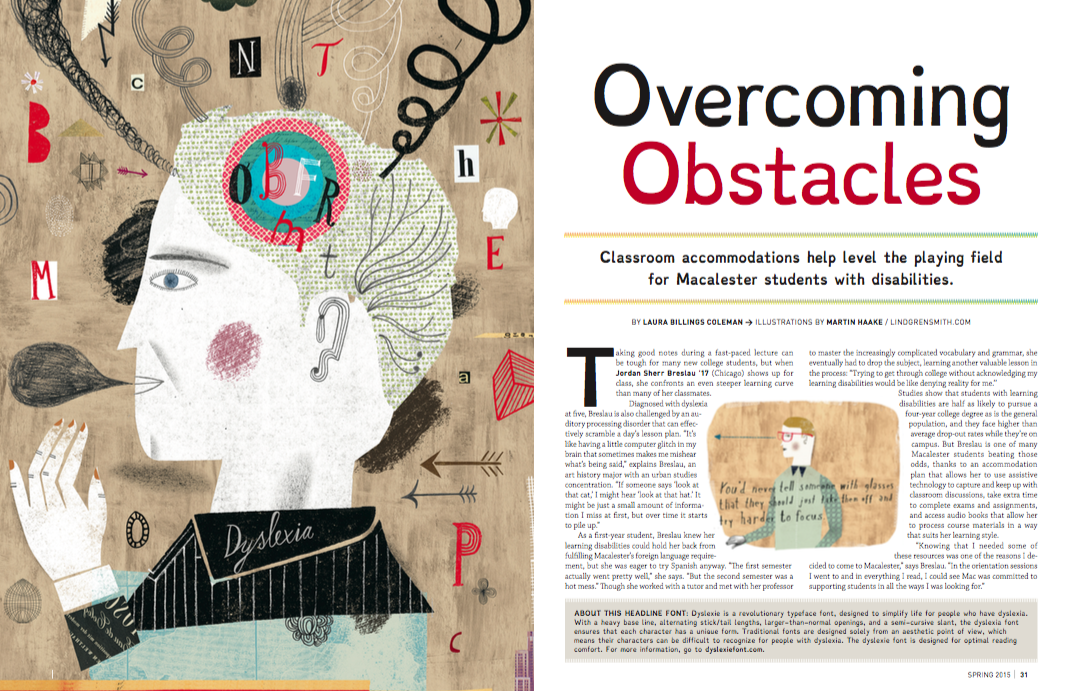

TAKING GOOD NOTES during a fast-paced lecture can be tough for many new college students, but when Jordan Sherr Breslau ’17 (Chicago) shows up for class, she confronts an even steeper learning curve than many of her classmates.

Diagnosed with dyslexia at five, Breslau is also challenged by an auditory processing disorder that can effectively scramble a day’s lesson plan. “It’s like having a little computer glitch in my brain that sometimes makes me mishear what’s being said,” explains Breslau, an art history major with an urban studies concentration. “If someone says ‘look at that cat,’ I might hear ‘look at that hat.’ It might be just a small amount of information I miss at first, but over time it starts to pile up.”

As a first-year student, Breslau knew her learning disabilities could hold her back from fulfilling Macalester’s foreign language requirement, but she was eager to try Spanish anyway. “The first semester actually went pretty well,” she says. “But the second semester was a hot mess.” Though she worked with a tutor and met with her professor to master the increasingly complicated vocabulary and grammar, she eventually had to drop the subject, learning another valuable lesson in the process: “Trying to get through college without acknowledging my learning disabilities would be like denying reality for me.’’ Studies show that students with learning disabilities are half as likely to pursue a four-year college degree as is the general population, and they face higher than average drop-out rates while they’re on campus. But Breslau is one of many Macalester students beating those odds, thanks to an accommodation plan that allows her to use assistive technology to capture and keep up with classroom discussions, take extra time to complete exams and assignments, and access audio books that allow her to process course materials in a way that suits her learning style.

“Knowing that I needed some of these resources was one of the reasons I decided to come to Macalester,” says Breslau. “In the orientation sessions I went to and in everything I read, I could see Mac was committed to supporting students in all the ways I was looking for.”

“Knowing that I needed some of these resources was one of the reasons I decided to come to Macalester,” says Breslau. “In the orientation sessions I went to and in everything I read, I could see Mac was committed to supporting students in all the ways I was looking for.”

Nationwide, more than two million college students—about 11 percent of the country’s undergraduates—have some form of disability. At Macalester last fall, approximately 5 percent of the student body requested accommodations through the college’s disability services programs. “When people hear the word disabilities, they often think of students with physical challenges, but those are the issues we see least,” says Associate Dean of Students Lisa Landreman, who works with juniors and seniors seeking accommodation plans. “Psychological disabilities such as anxiety, depression, or PTSD tend to be the most common issues for college students, followed by general learning disabilities.”

In fact, nearly three quarters of students who receive disability services do so because of psychological challenges—numbers that reflect the high rates of mental distress among adults aged 18 to 25. “A recent University of Minnesota study showed that more than 25 percent of students had received a mental health diagnosis at some point before entering college—and that’s a large number,” says Ted Rueff, associate director of the college’s Health & Wellness Center. But thanks to a new wave of medications, a reduction in the stigma once associated with seeking mental health treatment, and a generation of parents who have supported their children’s access to care, says Rueff, “we’re seeing a whole group of students succeeding now who might not have made it to college a generation ago.”

Removing Barriers

Removing Barriers

Designing accommodation plans for qualified students who contend with disabilities such as anxiety, ADHD, or autism spectrum disorders has become a growing trend at Macalester and other colleges across the country. The Americans with Disabilities Act requires post-secondary institutions to make “reasonable efforts” to provide qualified students equal access to all the courses, services, programs, jobs, and facilities on campus—a process Mac students must initiate through the Office of Student Affairs.

“The transition to college can be a challenge because the K–12 model is about success, while in higher education, the goal is access,” say Robin Hart Ruthenbeck, assistant dean of students. She is the first point of contact for first- and second-year students seeking accommodations. By law, elementary and high schools are obligated to identify students with disabilities and document their classroom needs, but in college, the responsibility for informing institutions and requesting services shifts to the student. To start the process, incoming students with disabilities might share their course schedules and academic plans with Ruthenbeck, and “together we look at the ways our systems, our structure, and the way we approach education here might create barriers. Then we look for ways to mitigate those barriers.”

For instance, a student in a wheelchair might need a classroom in a building with an accessible ramp, while a student with dysgraphia may be approved to use a laptop for lab assignments. The goal with any accommodation, says Ruthenbeck, is to avoid making one that compromises the integrity of the course. “The core of what needs to be accomplished in a classroom is still intact.”

Signing Up for Support

Even so, not every student who qualifies for accommodations seeks them. “Many students are tempted to make a fresh start, to try it without medication, counseling, or accommodations,” says Rueff. “A change of scenery can do you good, but wherever you go, you bring yourself. That’s why we advise students to stick with what worked in the past, and to seek out the support they need.”

The same go-it-alone impulse is often seen among students with learning disabilities, less than a quarter of whom inform post-secondary schools of their need for services, according to research from the National Center for Learning Disabilities. The same report found that just 17 percent of students with learning disabilities received accommodations and supports in college, compared to 94 percent who did so in high school.

The same go-it-alone impulse is often seen among students with learning disabilities, less than a quarter of whom inform post-secondary schools of their need for services, according to research from the National Center for Learning Disabilities. The same report found that just 17 percent of students with learning disabilities received accommodations and supports in college, compared to 94 percent who did so in high school.

Since students with disabilities must self-identify when they arrive on campus, it’s hard to know how many don’t pursue the services they’re entitled to. That’s why Ruthenbeck and others from the Office of Student Affairs reach out early and often to incoming students, encouraging them to get the support they need to succeed. “Our goal is to give students the tools they need, and I see accommodations as a tool,” says Ruthenbeck. “You’d never tell someone with glasses that they should just take them off and try harder to focus.”

Macalester offers a variety of tools that students— both with and without disabilities—are encouraged to tap. The Macalester Academic Excellence Center provides tutoring services and study tips, and arranges for proctors and approved testing spaces for students requiring accommodations. For instance, students with ADHD—who may need to move around while taking exams—can ask for a separate test-taking space that will allow them to avoid distracting their classmates.

Students may also access audio books and assistive technology, such as Kurzweil text-to-speech software, which makes classroom PDFs or recommended websites accessible to students with visual impairments or dyslexia. Students with hearing problems can use recording devices that cancel out white noise and amplify their professor’s voice. Through the ITS office, Breslau is experimenting with Livescribe, a “smartpen” that transfers her handwritten notes and recorded classroom audio into a digital format. The software even allows her to mark when she lost the thread of a classroom discussion, so she might later return to what she missed and make sense of it.

Although Breslau believes assistive technology helps her get more out of school, ITS liaison Brad Belbas notes that many students continue to resist it. “The idea of needing something to support their learning is not always a comfortable thought,” says Belbas, adding that “a surprising number of students arrive at Mac with severe learning disabilities that had gone undiagnosed until late in high school, students who have been so capable at adapting to their environment that they’ve been able to get by. It’s a great testament to their resilience.”

But the more intense demands of college coursework can often push struggling students to seek help for the first time. Not long ago, Belbas helped a student with an auditory processing problem set up a software service that provides real-time closed captioning of class lectures. “Just missing a cluster of 10 words in a graph meant that he’d have a lot of work to make up, trying to figure out what he was missing,” Belbas says, adding that trying the software was a revelation to the student. “He said it was the first time he’d ever walked out of a class and not felt instantly behind.”

Universal Access

Universal Access

To Macalester alumni who came of age in the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, this learning landscape probably looks very different from the college they remember. “A generation ago, there was an expectation that students with disabilities just had to suck it up and do things the way everyone else does,” says Joan Ostrove, chair of the Psychology Department. Although colleges were early advocates for access by disabled students, she says, “The passage of the American Disabilities Act [in 1990] really helped to raise the visibility of people with disabilities, and their right, as one observer put it, to boldly go where everyone else has gone before.”

In recent years, college campuses have also become important proving grounds in the Universal Design for Learning movement, a set of principles for curriculum development that asks educators to consider more flexible ways of presenting information and engaging students—for instance, setting hand-outs in type fonts large enough to be read by students with visual impairments, or providing lecture outlines before class, thus allowing students with dyslexia and other processing challenges to get the head start they need to participate in classroom debates. Simple shifts like these often benefit all learners—not just those with disabilities, says Ostrove.

“We are seeing students in college whom we would not have seen a generation ago, and that’s a good thing,” she says. “It gives us opportunities to think differently about how we do our work, how people learn, and how to maximize the flourishing of brilliance, which is really important.”

Ostrove covers some of this territory in Minding the Body, a course that Kate Gallagher ’16 (Tucson, Ariz.) credits with her decision to advocate for her own needs as a student with disabilities. Gallagher suffers from Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a genetic connective tissue disorder that causes chronic joint pain and occasional flare-ups that force her to attend class in a wheelchair. “That class was my introduction to disability as a social identity, and the first time I realized that not everyone else is in constant pain,” says Gallagher, who is now facilitator for Macalester’s Disability, Chronic Pain & Chronic Illness Collective.

“At first, identifying as disabled was kind of hard for me, but it ended up being a necessary resource,” she says. “Nobody has an easy time getting through college, but my disability puts me farther away from the starting line and therefore farther from the finish line.” Now Gallagher has an accommodation plan in place that allows her some flexibility on class attendance and deadlines during flare-ups, and the freedom to fulfill her campus work-study job tasks in a ground-floor office on those days when climbing stairs is out of the question.

While all these efforts have enabled her to stay enrolled at Macalester during some stressful times, says Gallagher, the accommodation that has helped her the most is simply being allowed to sit down during choir practice. “You never see a singer sitting—it’s not the optimal way to do it. But the fact that we’ve created this accommodation that allows me to participate in something I love to do has meant the world to me,” says Gallagher. “It’s not always easy to advocate for yourself, but if it helps you learn, it can be life-changing.”

LAURA BILLINGS COLEMAN is a regular contributor to Macalester Today.

Another great story by a great writer…thanks, Laura!