From the archives

Nick Coleman, a slow learner, has raised three more hockey players since this article appeared in Minnesota Monthly in March, 2001.

I was nuts. Just like most hockey moms and dads.

We start out with good intentions and then we slowly go insane.

My son’s hockey coach was on the phone, explaining why my kid had been benched and hadn’t skated in the last two games.

“Your son isn’t hungry enough,” the coach said in a bored tone, like a mechanic telling me I needed a brake job. “I want guys to crash the net and go after the puck like they want it more than the other team. If one of my players ain’t hungry, he’s not going to get much ice time. It’s that simple.”

My boy was in 4th Grade. Nine years old. A nine-year-old shouldn’t be hungry. A nine-year-old should be nourished. I put down the phone. My hate affair with hockey had begun.

Hockey is the prestige sport of Minnesota, part of my heritage and part of the mythology of my state, a game I played on the outdoor rinks along West Seventh Street in St. Paul when I was growing up, a game I wanted to share with my children. But something is rotten in “the State of Hockey.”

You don’t have to lose teeth or get stitches to receive hockey scars. All of my children have played hockey and all carry the marks of the game – the good and the bad, the highs and the lows – with them.Sometimes, it’s wonderful. Other times – too often – it’s too much. Too much pressure, too much at stake, too much money and time invested, too many adults trying to live through the accomplishments of their children. Too much of everything except the one thing hockey was supposed to be: Fun.

I have spent years as a coach, a ref, a coordinator, a parent and – on a thousand Monday nights when I have gotten together on the ice with my pals – a player. So, like almost every hockey parent I have known, in a state where almost 60,000 kids play hockey, I both love and hate hockey.

Hockey can be exhilarating and joyful, a game that allows its players to feel free of the restraints of gravity and friction, a game that lets you dance on ice and experience the joy of physical release. It can also be a nightmare: A violent, dangerous game marred by politics, parents and coaches interested most in their own success.

So far, Minnesota has not experienced an incident such as the one last summer in which in Massachusetts, where one hockey dad beat another to death after becoming enraged during a youth hockey scrimmage. But that is just dumb luck. Many hockey parents, if they were honest, would acknowledge harboring homicidal impulses. I never killed anyone during more than 20 years of involvement in youth hockey. But I would have enjoyed knocking some sense into a few fellows.

Like the guy who told me my son wasn’t hungry enough. Or the bully of a big kid who would punch my son when he thought no one was looking. Or the parents of my daughter’s hockey teammate who got angry with me when I was a volunteer coach and their sweet little girl told me to go perform an unnatural act on myself and I made her sit out a few shifts to think about it. Or the guy – a friend who had a big job at the University of Minnesota – who climbed the glass at a junior varsity game, eyes bulging, face turning beet red, to scream obscenities at the ref for calling a penalty on his son, who had just poleaxed a player half his size.

I won’t leave myself out of the litany. I have done enough stupid things in hockey to deserve a good clout myself.

There was the time, for instance, that my oldest boy, 10 at the time, complained that his thumb hurt after a game. He had gone done in a heap of kids near the end of the game. I examined his thumb in the dim light of the locker room but could see nothing wrong with it. He continued to complain but I told him to “shake it off,” silently wishing that he might be a little tougher and, yes, hungrier. Hours later, annoyed that he was still cradling his thumb with his other hand and wincing, I impatiently looked at it again. This time, in brighter light, I could see the inch-long sliver of wood that had come off some kid’s hockey stick in the end-of-the-game pile-up and jammed itself through a hole in his hockey glove, plunging deep under his thumbnail, all the way to the cuticle. As I drove to the emergency room, I nearly threw up.

The phrase “hockey parent,” in an era when fisticuffs in the stands have become commonplace, has become a shorthand for “overly involved, kid-pressuring maniac.” Most hockey parents have something related to the game that they can be ashamed of. We develop tunnel vision and focus tightly on our kids, resenting the other kids’ successes if they interfere with our kids’ opportunities. We live vicariously through our children’s exploits. We buy into the criticism of our kids. Although I was angry with the coach who said my boy wasn’t hungry enough, I found myself blaming my son after games for not doing better, urging him to try harder. I started getting a knot in my stomach when he played.

This wasn’t what I signed us up for.

He wasn’t the most gifted or skilled athlete (he was my son, after all). But he was a great kid and he loved hockey. By age 7, he was a committed puck head. He would spend hours in the basement after school, propping his little brother (who was still in diapers) in front of a floor-hockey net and shooting tennis balls at him, celebrating every goal, cheering his little brother’s every inadvertent save, rattling tennis balls off the wall paneling, knocking down ceiling tiles with a stick raised in triumph, calling each play: “He shoots, he scores!!! Not hungry enough? He was ravenous. For fun. That’s all he wanted: To play.

He went on to play on a sort of junior varsity team in college, but there was no free ride. I would have been wiser to have put my hockey expenditures in a college savings account. During his 10-year youth hockey career, from second grade through senior year in high school, I probably spent $12,000 on his hockey training, including off-season training that involved a treadmill of artificial ice on which the boy, suspended in a harness from the ceiling – had to skate backwards and uphill as fast as he could. It didn’t look like hockey; it looked like a torture scene from a James Bond movie. Do you want me to skate uphill and backwards? No, Mr. Bond. We want you to die.

Throw in all the money spent on those mid-winter getaways for hockey tournaments to Albert Lea, Duluth and Mora and I understand why I never could afford that Caribbean cruise.

I was nuts. Just like most hockey moms and dads. (Or parents of gymnasts, swimmers, dancers or basketball players. Hockey is not alone in the toll it takes on families). We start out with good intentions and then we slowly go insane.

I spent years hauling my kids to arenas. I have been inside more than 100 ice arenas in Minnesota. Some people have life lists of the species of birds they have seen, or the state capitols they have visited. I have a life list of Zambonis.

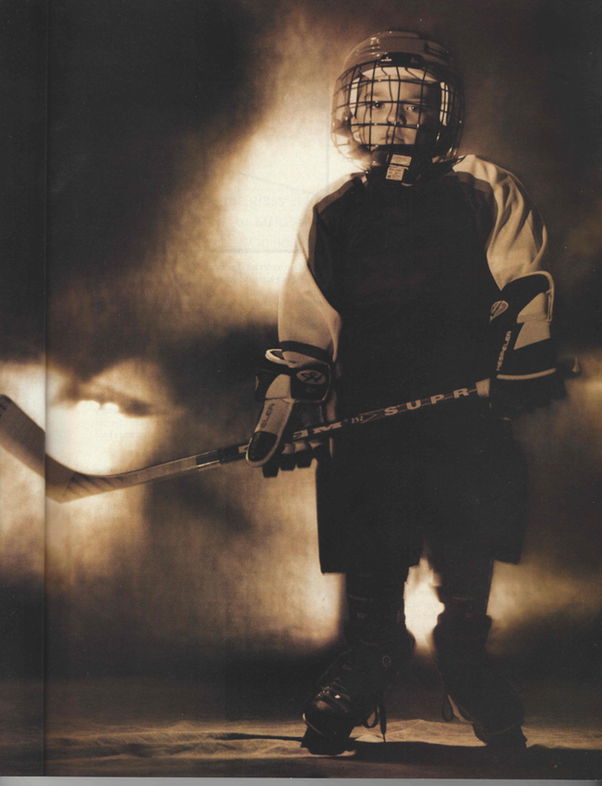

One year, I put together a computerized hockey schedule for the season for my three children then on skates. From November to February there were 225 on-ice events, all of which involved someone being dropped off, picked up, or both. For years, I had calluses on the outsides of my little fingers from tightening skate laces thousands of times. Plus photo magnets on my file refrigerator, button snapshots of my children on ice. One of those buttons shows my kids all together, wearing the same goofy grin. It’s the closest tangible thing I have to demonstrate what I from all those grueling years in youth hockey as a family: Memories of us, together.

Kids are required to play hockey year around if they hope to be able to play in the prestigious Minnesota high school league. With practices, skill camps, and games (a high school hockey player easily can spend 300 supervised hours on the ice every year), most kids don’t have the time or energy to go down to the park on their own and play that oldest and purest form of hockey the unorganized and fun game known as “shinny” or pond hockey – where kids play without refs, coaches, or parents, and where they used to learn more creative hockey than most of today’s over-regimented players ever do.

Those unused outdoor ice rinks have become a disturbing sight to lovers of hockey. If hockey is our game, why aren’t the kids skating on the free ice?

“There should be more fun put back in the game,” says Doug Johnson, publisher of “Let’s Play Hockey,” a Minneapolis-based hockey newsweekly that is distributed at sporting goods stores and ice arenas around the state, and which is read by almost everyone who owns hockey skates.

Johnson, a standout hockey player at Minneapolis Roosevelt High School in the early 1970s who played for the University of St Thomas and in the minor professional leagues, hasn’t yet signed up his 7-year-old son, Devon, for the intense world of indoor hockey. Instead, he takes Devon down to the neighborhood park to skate almost every winter night.

“I just want him to play for the fun of it right now,” Johnson says. “I want him to learn the skill-development part of the game, but I don’t want him to feel he has to play. As long as he’s having fun and wants to keep at it, we’ll do it. But if he doesn’t want to, that’s it. There’s a burnout factor today from all the off-season hockey. The other day, a parent whose kid plays on an all-star team was telling me that on a day off from school, he couldn’t get one kid on the team to go down to the park and play tennis-ball hockey. Not one. If I could be Hockey God for a day, I’d tell parents their kids should play for the fun of it and not to play every game like it’s a life-or-death thing.

But hockey can be a life-or-death thing. Two Minnesota high-school-age players have suffered catastrophic injuries in recent years, and many others have had concussions, broken bones, ruptured arteries and other major injuries.

“Hockey has always been a rough-and-tumble game, but it was not quite as brutal back when I was playing as it is now,” says Dr. William O. Roberts, a physician with the MinnHealth Family Physicians clinic in White Bear Lake who played hockey as a boy in Rochester. He is one of a growing number of doctors concerned about the rising injury rate in hockey.

Today’s players wear protective padding that makes them feel invulnerable to injury, Roberts says. But they also are bigger and faster – and often more reckless – than players of earlier generations who were forced to worry more about protecting themselves and played more cautiously.

Referees, too, have changed., Roberts says; today, referees consider as routine plays that would have been penalized 30 years ago. Hockey players now are pressured to put “big hits” on their opponents, Roberts says. Big hits lead to big injuries.

“Most people aren’t aware of the risks involved in ice hockey,” Roberts says. “The weak link is the neck. You can break your neck skating at walking speed. Well, the average Peewee player (ages 12-13) can skate at 20 miles per hour. Necks just can’t withstand an injury at that kind of speed.”

Many doctors – including the Academy of Pediatricians – are calling for a ban on checking for all hockey players under the age of 16. Girls’ hockey already prohibits checking, but that doesn’t take all the danger out of the game. The all-time leading scorer in Minnesota girls’ high school hockey, Roseville’s Renee Curtin, was knocked to the ice in a game last season. She suffered a broken neck, a concussion, and amnesia.

“Hockey is a game of great beauty and skill, if it is played the way it was intended to be played,” says Roberts , who has helped provide first aid at the Minnesota high school hockey tournament since 1984. “Every time I see someone go down, I wonder if they’ll get up. I think they’re encouraged to hit hard because that’s the way they get the coach’s attention and move up. But there’s no necessity for all the hitting. If we took it out, we might have a better game.”

A better game. That’s what I had wanted for my daughter when I cajoled her into trying girls’ hockey when she was in 5th grade. She loved it as much as her big brother did. After her first game, in which she used an elbow to rattle the helmet of an opponent, her face was flushed with excitement: “Dad, did you see me hit that girl?”

I had, and didn’t like it. But I loved her enthusiasm. Thus began an eight-year roller-coaster ride of excitement and disappointment, tears and joy. She became part of the boom in girls’ hockey, scoring the first-ever goal for a new high school team while just an 8th grader. Her picture was in the newspaper. Hockey was wonderful.

She also was also treated cruelly by irresponsible adult coaches more concerned with how they looked than with how their players did. She hung on through high school, learning life lessons I wish she hadn’t had to learn the hard way – lessons about persistence and patience and humility. But not before, in her last season, I became just another hockey dad from hell.

It was her senior year and, after bouncing back and forth between the junior varsity and senior varsity teams for three seasons, her spot on the varsity finally seemed secure. She had worked hard during the summer, exercising, taking power skating lessons, playing summer league. She was looking good, and looking forward to her final season of youth hockey. The team won its first game but the coach was dissatisfied and thought it should do better. Although my daughter had played well, he moved her down to the JV so that a younger, “hungrier” player could move up. My daughter was in tears.

I was in a mood to kill. This was my daughter they were messing with.

I called the coach and called him names I didn’t learn in journalism school. I cursed his ancestors and threatened to torch his home and hobble his cattle. I indicated a familiarity with the practice of witchcraft. I got what I wanted: He realized the error of his ways and reversed his decision.

I had become what I had hated 10 years before.

Hockey can make people crazy a lot faster than that.

In Canada, where hockey is both national pastime and a passion, youth hockey registration has dropped sharply over the past decade – from 120,000 players to 90,000. Referees have been quitting in record numbers, and brawls have broken out in the stands between parents attending youth games.

Now, the Canadian government is poised to hold public hearings on the issue of violence in hockey. Coaches have been accused of sexually abusing young players; in widely publicized “hazing” scandals, players in Canada’s rough-and-tumble junior hockey leagues were found to have sexually abused other players in bizarre initiation rites. (Last season, the University of Vermont suspended its hockey program after hazing charges surfaced there.)

Canadian journalist Laura Robinson, author of “Crossing the Line: Sexual Assault in Canada’s National Sport,” has gone so far as to suggest that hockey is suffused with an ethos of sexual exploitation.

Violence, injuries, abuse, high costs, crazy demands on families, angry parents. Sounds like fun, eh?

OK, so maybe I’m nuts. But still, deep down, I love hockey. The reason is hockey’s dirty little secret: It is really, really fun. The game, at its best, is pure pleasure: Speed, grace, agility. Blades on ice, sticks and pucks, putting the biscuit in the basket. I had forgotten how much fun it was until my oldest child started to play and I dug my old skates out of the closet and went down to the rink with him and started – after a 20-year hiatus – to play again.

Since then, I have played every week, all year around. I carry my skates and a bag of pucks in my car at all times. I have watched boys’ and girls’ hockey. I have been a referee. My youngest child is still playing hockey in high school; that kid in diapers who used to let his brother bounce tennis balls off his head is now a goalie who, when he skates onto the ice, wears almost $4,000 of equipment. I share season tickets to Gophers hockey games, and I have been to dozens of Minnesota Wild games. But when I want to have real fun, I get together with a bunch of has-beens and never-weres at a local arena to play a game that was supposed to be for kids.

Too bad it’s just us geezers who seem to be enjoying it. More and more men – and women, too – are playing hockey for fun into their 50s, 60s and even later. And they are rediscovering something we adults have taken away from the kids’ game: The fun of it. That’s all I play for. We don’t keep score. We don’t keep grudges. We don’t have practices. We just play.

Sometimes now, when my older children are home from college and my young goalie has a day off from school and can stay up late, I drag them all to the arena after the youth teams are done for the night, and we all get to play hockey together, like I always wanted: No scoreboard, no refs, no screaming parents.

Except for me. And I’m not screaming, really. I’m laughing.

One day, I hope my children all will laugh with me. I hope they will all be great geezer hockey players. Then, their fun will begin.

This was a good article then and still holds true today. Hope all is well with you and Laura