About This Project

“Schools come after Law and Government,” wrote Henry Taylor, who quit a teaching job in Belle Prairie, Minn., near modern-day Little Falls, to join the volunteers. “‘The Star Spangled Banner, O Long May it Wave.’ I go feeling that I am in the right and in a good cause, and if that be the case, I will not fear. Tell all my brothers and sisters to stand firm by the Union and by the glorious liberties which, under God, we enjoy.”

Five of Taylor’s brothers would join him in the war, including Isaac, who also volunteered for the First Minnesota and would die at Gettysburg .

Gettysburg and the First Minnesota remain a profoundly moving story. You can read about all the grand strategies and everything, but the extraordinary thing about the First Minnesota is that when they stood on Cemetery Ridge that day and heard the order to charge, they knew exactly what that meant, and yet they didn’t hesitate. They knew most of them would not survive, and yet they went forward.

Roger MoeThere is no more gallant deed in recorded history. I ordered those men in there because I saw I must gain five minutes’ time. I would have ordered that regiment in if I knew that every man would be killed. It had to be done, and I was glad to find such a gallant body of men at hand willing to make the terrible sacrifice.

Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock

Series by Nick Coleman

Part 1

July 2, 1863

No More Gallant Deed

On a sweltering Pennsylvania day, 135 years ago today, a tight-knit band of 262 Minnesotans – survivors of the 1,000-man regiment distinguished as the first volunteer regiment raised to fight for the Union – stood and waited on a hillside called Cemetery Ridge, watching the tide of war turn against everything they believed in.

The Union. The Flag. Freedom. Home.

As the remnant of the once-strong First Minnesota cradled its rifles and gazed grimly across a dry creek towards a peach orchard half a mile away, Robert E. Lee’s Confederate soldiers were turning the battle of Gettysburg , on this, its second day, into a disaster for the North. If the Confederate forces gained the top of Cemetery Ridge, they would turn the Union flank and drive the Union Army all the way back to Washington or Philadelphia.

The war might be over then, with the Emancipation Proclamation, barely 9 months old, not worth the paper it was written on, the slaves still in bondage, and the Union gone forever.

But that’s not how the story came out. The First Minnesota soon would charge headlong into the crossroads of history, laying its life and honor in the way of defeat.

While the battered First Minnesota waited, held in reserve, it watched the Union troops break and flee the field, the panic-stricken Northern troops running through the ranks of the waiting Minnesotans. The First Minnesota did not join the retreat.

“The First Minnesota had never deserted any post, had never retired without orders,” one Minnesotan wrote later. “Desperate as the situation seemed, and as it was, the regiment stood firm against whatever might come.”

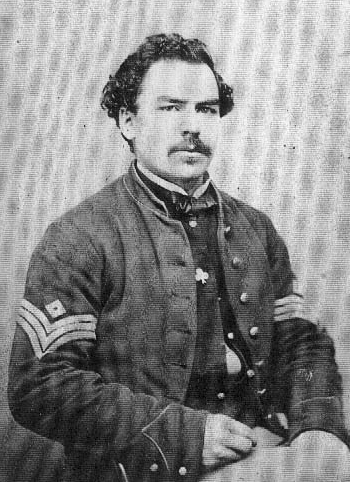

“I never felt so bad in my life,” Sgt. John Plummer would write after the battle, of watching the other Union troops panic and run from the advancing Confederates. “I thought sure the day was gone for us, and felt that I would prefer to die there, rather than live and suffer the disgrace and humiliation a defeat of our army would entail on us, and if I ever offered a sincere prayer in my life, it was then, that we might be saved from defeat.”

Sgt. Plummer’s prayer would be answered. The Union would be saved from defeat that day, July 2, 1863. By the bravery of Plummer and his comrades who, without hesitation, made a suicide charge against a vastly more powerful opponent in order to buy enough time for Union commanders to bring up reinforcements and turn the tide.

They succeeded, but at a cost that would shock and sadden the new state of Minnesota, which two years earlier had sent its soldiers off to war with parades, prayers and aching hearts. When the awful day was over, only 47 of the Minnesotans had come through unscathed; 215 lay dead or wounded on the field that President Abraham Lincoln, four months later, would declare consecrated by the valor of those who fought there.

This is their story, as best as we can tell it.

And yet they went forward

“The Civil War was the formative event in our nation’s history,” says Richard Moe, whose 1993 book, “The Last Full Measure: The Life and Death of the First Minnesota Volunteers,” is the best account of the famous regiment. “There are 100 million Americans who have ancestors who fought in the Civil War; it’s hard for us to understand how profoundly it has affected every family.”

The effect of the war was seminal and formative in Minnesota. Almost 60 percent of Minnesota men of service age joined the Union Army – 25,000 of the 40,000 men eligible for duty. Of that number, 10 percent were killed or wounded and thousands more had their lives changed forever.

For Minnesota, as for the country, the story seems to reach its climax with the epic battle of Gettysburg , a bitter three-day fight that was the largest battle ever fought in the Western Hemisphere, pitting almost 160,000 men in a contest that would ultimately represent the “high-water mark” for the Southern rebellion – the beginning of the end of a war for the soul of the nation.

The First Minnesota, as history shifted 135 years ago, was at the fulcrum. It will be there again this week in spirit as well as in symbolic recreation. Almost 50 Minnesotans – members of a Civil War re-enactment group that portrays the First Minnesota Regiment – will arrive in Gettysburg today for a three-day, full-scale recreation of the battle, beginning Friday and running through Sunday.

With more than 15,000 Civil War re-enactors expected to participate in the mock battles, the Gettysburg re-enactment is being billed as the largest gathering of the Blue and the Gray since the Civil War ended in 1865.

Commanded by Capt. Keith Gulsvig, a 41-year-old photographer and computer programmer from Champlin, the reconstituted First Minnesota’s ranks will be bolstered by hundreds of other re-enactors wishing to become – if only briefly – part of the fabled regiment.

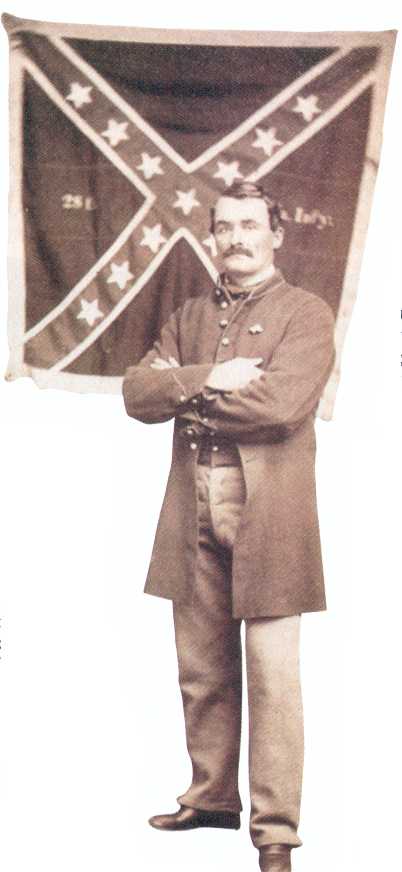

On Saturday, the second day of the re-enactment, they will commemorate the desperate charge of the First Minnesota in which 82 percent of the regiments’ soldiers were killed or wounded – traditionally recognized as the largest one-day loss of any Union regiment in the war. And on Sunday, the First Minnesota will re-create the astonishing feat of the surviving fragment of the regiment, when the Minnesotans engaged in frenzied hand-to-hand combat with Confederates at Pickett’s Charge, and captured the battleflag of the 28th Virginia Regiment.

Oh, yes. That flag.

While re-enactors from Minnesota and Virginia meet on the battlefield to re-stage its historic capture, the attorney general of the state of Minnesota is still considering a formal demand to return the original flag – captured July 3, 1863, and now stored at the Minnesota Historical Society – to its native soil.

Just because the Civil War is history doesn’t mean it’s over.

“ Gettysburg and the First Minnesota remain a profoundly moving story,” says author Moe, a former aide to Vice President Walter Mondale, who now serves as head of the National Trust for Historic Preservation. “It was a climactic battle, filled with great dramas and tragedy, and it was the decisive battle of the war. The experience of the First Minnesota was absolutely critical. There were other critical parts in the battle, but the First Minnesota’s experience exemplifies the courage and valor that made a difference for the union.

“You can read about all the grand strategies and everything. But when you read about the men who suffered so grievously, you can’t help but be moved. The extraordinary thing about the First Minnesota is that when they stood on Cemetery Ridge that day and heard the order to charge, they knew exactly what that meant, and yet they didn’t hesitate. They knew most of them would not survive, and yet they went forward.”

Stand firm by the Union

Minnesota’s Alexander Ramsey, the second governor of the 32nd state of the Union (admitted in 1858), was in Washington, D.C., on April 13, 1861, when word came that Fort Sumter, S.C., had been captured by Southern rebels.

The long-feared war had come, and Ramsey was the first governor to offer troops to the Union, promising to raise a regiment of 1,000 volunteers on the Minnesota frontier.

There is little evidence there was any rejoicing in the streets of Washington when news came that far-off Minnesota might send some soldiers to aid the Union. Few, in 1861, thought the war would be long or that a regiment of Minnesotans would make any difference. But out on the prairie farms and in the woods and fledgling cities of Minnesota, men flocked to sign up.

Whole companies enlisted from St. Paul, St. Anthony (Minneapolis) and Stillwater. Farmers, lawyers, woodsmen took the oath, joined the new regiment at Fort Snelling, and signed on for three years.

By today’s standards, the reasons for their enlistments seem almost quaint, or hoary. God and country, flag and freedom. Honor. And, above all, the idea of preserving the union, something we take for granted in 1998, but which was in peril then.

“Schools come after Law and Government,” wrote Henry Taylor, who quit his teaching job in Belle Prairie, Minn., (near modern-day Little Falls) to join the volunteers. “`The Star Spangled Banner, O Long May it Wave.’ I go feeling that I am in the right and in a good cause, and if that be the case, I will not fear. Tell all my brothers and sisters to stand firm by the Union and by the glorious liberties which, under God, ween joy.”

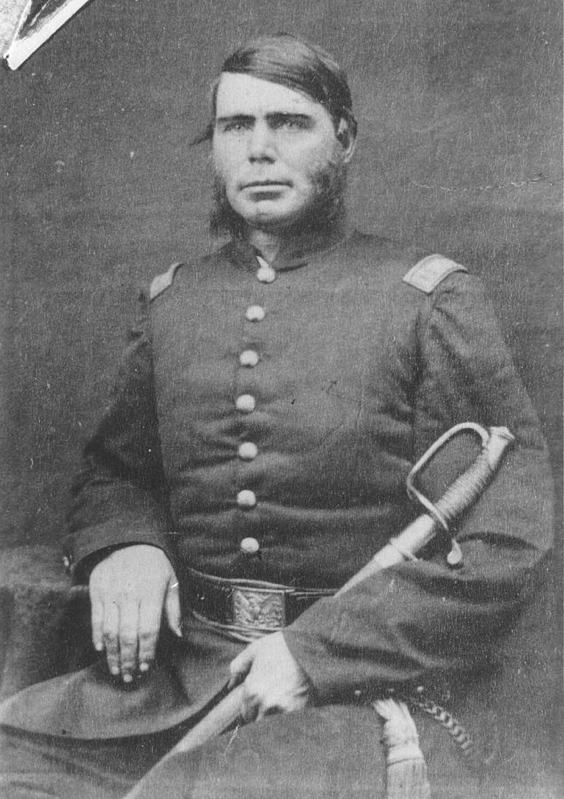

Five of Taylor’s brothers would join him in the war, including his brother Isaac, who also volunteered for the First Minnesota. Isaac would die at Gettysburg .

But in the first flush of enthusiasm, the First Minnesota cut a dashing look on its journey east, towards war. Traveling by riverboat down the Mississippi, the regiment paraded and partied in cities along the way, transferring to a train at LaCrosse, Wis.

By the time the regiment reached Chicago, it already had a flamboyant image, burnished by the gaudy red wool jackets and slouch hats the regiment wore at first, sartorial touches it would soon give up in favor of regular army uniforms and forage caps.

A Chicago newspaper raved about the appearance of the First Minnesota after it had marched through the streets of that city while transferring trains: “There are few regiments we have ever seen that can compare in brawn and muscle with the Minnesotians, used to the axe, plow, rifle, oar and setting pole. They are unquestionably the finest body of troops that has yet appeared on our streets.”

The pomp and the parades soon ended. In Pennsylvania, the First Minnesota was transferred from comfortable passenger cars to cattle cars for the rest of the trip to Washington, supposedly as a precaution against being sniped at by Confederate sympathizers in Maryland. Instead of cheering crowds, they found a surly throng, and marched through Baltimore with their weapons loaded.

“We were approaching a region where soldiering was less of a holiday matter than it had been with us,” the regiment’s William Lochren wrote.

On the 21st of July, 1861, the First Minnesota saw its first action at the battle Northerners called Bull Run and Southerners called Manassas. The unit fought hard, but without cohesion, and suffered the highest percentage of casualties of any Union outfit in the battle, which the Confederates won. Twenty percent of the thousand-strong regiment lay dead or wounded.

The transformation that would turn a frontier state’s untried volunteers into one of the most elite and battle-hardened units in the Union had begun.

Bull Run. Edwards’ Ferry. Antietam. The Peninsula. Fredericksburg. Chancellorsville. By the middle of 1863, the First Minnesota had more than a dozen bloody clashes commemorated on its battle flag and the easy swagger of the first months in uniform had been replaced by a grim and weary determination to fight on.

There was an almost idyllic respite after the battle of Fredericksburg, when the armies of both North and South rested along the Rappahannock River in Virginia, within a well-aimed rifle shot of each other. The First Minnesota, which by this time had been whittled down by battle and disease to about 330 men, enjoyed the rest. They even traded newspapers, coffee and tobacco with Rebel soldiers, making toy sailboats to carry the trade goods over the river.

The fun was not to last. Gen. Robert E. Lee was going to take the war to the north.

Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia began moving north, down the Shenandoah Valley. The Union forces, moving north with Lee, staying between the Confederates and Washington, D.C., shadowed him. The veterans of the First Minnesota marched at the rear of the column, miles behind the head, jostling along the roads with the army’s surgeons, sutlers, servants and other noncombatants. They had been at war for two years – two-thirds of the way through their three-year enlistments – and were bone-tired.

“Sometimes I think I will turn Quaker or some other harmless sort of animal and live at peace with all mankind,” Edwin Walker wrote. “But unfortunately (or otherwise) I am in for three years and perhaps it will be best to be belligerent during that time.”

By June 29, after a sizzling one-day march of 33 miles, the First Minnesota was in Maryland, near the Pennsylvania state line. Regiment commander Col. William Colvill was under arrest, having been stripped temporarily of his office by a general. When the regiment had come to a creek spanned by a narrow foot-bridge, a general had commanded the men to wade through the water instead of using the bridge, which required balancing while crossing it one foot ahead of the other. Some Minnesotans ignored the order, not wanting to get their shoes wet, which would mean agonizing blisters on the rest of the march. When some soldiers also booed the order (the Minnesotans said it was troops from a Massachusetts outfit), the general put Colvill under arrest and made him walk at the rear of his troops.

The never-ending war

“In the heat of battle, anything can happen, and I’ve seen some things that have scared me,” says John Guthmann, a 43-year-old St. Paul attorney who has been part of the First Minnesota re-enactment group since its founding 25 years ago.

There was the time, for instance, when a re-enactor stumbled and somehow managed to bayonet himself in the leg. And the time after a battle re-enactment when Guthmann encountered a Confederate re-enactor and discovered the man had been carrying a gun loaded with live ammunition instead of blanks.

“It takes a high level of trust to do a re-enactment,” Guthmann says dryly.

On top of the possibilities of accidents and injuries, there is also the occasional embarrassing moment when re-enactors get themselves into tactical fixes that no real Civil War soldier would have tried. Guthmann remembers one hillside engagement when the commanding officer ordered the First Minnesota to drop to the ground and continue firing at the Rebels. Since they were standing on a steep hillside, this meant the Minnesota regiment comically found itself on its belly, the heads of the men pointing downhill, their backs exposed as easy targets for the Confederates.

“That’s the only time I’ve ever seen where a man could get shot in the back while facing the enemy,” Guthmann says.

“When you think about what a cushy life we lead, it’s such a stark contrast to how those soldiers lived back then,” says Guthmann, who started out in the re-enactment field in college when he worked for the Minnesota Historical Society at Fort Snelling, portraying an 1820s-era soldier.

“And then you think about having a cause, and being not only willing to die for it but to volunteer to die for it. People fighting for an ideal – as time goes by, and we have more peace, that’s something you admire more than you have a chance to live in your own life. It makes you wonder if we could do it again, if we had to.”

The eve of battle

By the night of June 30, the road-weary troops, fatigued from weeks of marching in all conditions, lay down in a Pennsylvania farm field to sleep. “We remained quiet,” Lt. William Lochren said, “and made out the bi-monthly muster rolls, on which so many were fated never to draw pay.”

The next day, July 1, the echoes of distant cannons filled the warm air, and the First Minnesota moved towards Gettysburg and fame.

Part 2

Morning came early for the men of the First Minnesota Volunteers on July 2, 1863.

Roused from a fitful slumber at 3 a.m., the regiment was ordered to pack up and move up the road a few miles to a place called Gettysburg , where fighting had begun the day before between Robert E. Lee’s Confederates and Gen. George Meade’s Union forces.

For weeks, the First Minnesota – reduced by two years of warfare from its original complement of 1,000 men to just over 300 – had been on the march, shadowing Lee’s Confederates from Virginia through Maryland and now into the fertile, rolling farm country of central Pennsylvania.

There Lee hoped to win a convincing victory on Northern soil and force Abraham Lincoln to end the war, sealing the secession of the South from the Union.

It had been a brutal march, a stamina-draining ordeal in scorching heat, dust-choked roads and, just for variety, mud.

“I lay down in the rain without supper, but plenty of mud,” a Minnesota soldier named Henry Taylor wrote in his journal along the way. Scores of Union soldiers had dropped dead from heat stroke and the combined effects of hunger, sickness and exhaustion.

They had been beaten repeatedly by Lee’s rebels, most recently at Chancellorsville and Fredericksburg. Now the rebs were boldly striking at the North, hoping to win the war and end the idea of the United States.

In most of the battles the Confederates had won south of the Mason-Dixon line, the Southerners were outnumbered but fought with more ferocity and determination to defend their native soil.

Now, the tables were turning; the fight was moving North. This time – with the two great armies almost evenly matched – the Union soldiers would be defending their part of the land. The question that hung gloomily over the Northern columns as they tried to keep pace with Lee’s advancing army was simple: Could Northerners fight with the courage and intensity that the Confederates had demonstrated time and again?

Logistical nightmare

War is hell. Re-enacting it is no picnic, either.

One hundred and thirty-five years after the titanic struggle that changed the course of the Civil War, the little town of Gettysburg , Pa., is bracing itself for another epic meeting between the Blue and the Gray. This time, the soldiers are arriving by tour bus.

It is expected to be the largest Civil War re-enactment ever: Some 15,000 re-enactors, including 600 mounted cavalry troops and crews to fire 135 cannons, will recreate such famous Gettysburg fights as the battle for Little Round Top, Pickett’s Charge and Culp’s Hill.

In addition to the costumed combatants, an even larger army of spectators – as many as 35,000 – will descend on Gettysburg today for the start of the three-day event that will replay the pivotal battle that was fought here July 1-3, 1863. This time, without the carnage, God willing.

The logistics of such a re-enactment could have confounded Robert E. Lee.

Originally, many of the re-enactors had planned to march to the battlefield along the same roads the original armies took 135 years ago. Event planners, however, quickly realized the roads around the battlefield would become a nightmare if 15,000 marching men were added to the bumper-to-bumper car traffic.

So they put out an urgent advisory: All re-enactors must travel to their battlefield positions by bus.

Gridlock at Gettysburg is not the only potential problem.

Other possible dangers include heatstroke – a re-enactment at Bull Run had to be suspended when nearby emergency rooms started overflowing with stricken re-enactors – and too-enthusiastic sword play: “Overly aggressive `hand-to-hand’ saberfighting is forbidden,” reads Rule 32 for re-enactors.

“Breaking someone’s sword or knocking someone off his horse is not an example of manhood but of selfishness and stupidity and will not be tolerated.”

Cemetery Ridge

The men of the First Minnesota already had distinguished themselves in almost every major battle of the war, which was 2 years old and close to stalemate. But the regiment, weakened by losses, had been far from the sound of cannons that had echoed from Gettysburg on July 1.

The regiment commander, Col. William Colvill, a lawyer from Red Wing, Minn., had narrowly escaped death on the march north, when his horse was shot from under him during a brief Confederate artillery attack. Now Colvill was under arrest, stripped of his command by a superior officer who was outraged when some Minnesota soldiers, hoping to avoid blistered feet, had disobeyed an order and taken a foot bridge over a creek rather than wade across to save time.

Exhausted, hungry, angry over the way their commanding officer was treated, the men of the First Minnesota packed their haversacks and as the sky began to lighten, began trudging towards the front lines, knowing that 70,000 Confederate soldiers lay somewhere ahead.

Reaching a hill whose name – Cemetery Ridge – would later be known around the world, the men were posted in position before 6 a.m. and listened as a general’s orders were read aloud: This is going to be the great battle of the war, the general’s words informed them. Any soldier who leaves the ranks will be executed.

The threat had a reassuring effect on the battle-weary Minnesotans. At last, it seemed, the whole Union army was going to take this thing seriously. “We all felt better after hearing it,” wrote Sgt. John Plummer. “One thing our armies lack is enthusiasm.”

`No Lincolns’

Enthusiasm is not in short supply this weekend.

One of the most pressing problems at Gettysburg is the possibility of a glut of impressionists who attend these events portraying generals, journalists, society women and other historic personages.

To try to control the brigades of impersonators, organizers are requiring registration and limiting performances to approved areas. Most important of all, they have issued a strict ban on the era’s president. “No Lincolns, please,” reads Rule No. 4. “He was in Washington.”

For re-enactors, going through the motions of a Civil War battle is a powerful, sometimes grueling, way to understand war and the men (and occasionally women – more on that later this weekend) who fought it.

As interpreters of the past they consider it a badge of honor to go whole hog – to be as authentic as possible.

“You get a very, very good sense of what they went through,” says Keith Gulsvig, a computer programmer from Champlin, Minn., who is captain of a contingent of about 50 Minnesotans who arrived in Gettysburg yesterday to portray the famed First Minnesota Regiment.

“Obviously, we’re not infected with lice and we’re not starving to death and we don’t have real bullets screaming past our heads,” Gulsvig says. “But we use Napoleonic tactics, we march in columns, we learn about camp life … The sounds and the scenes are pretty much the same. There’s no way you can be exact, but you can try.”

Sometimes, re-enactors say, they experience a “rush,” a powerful emotional surge that makes them feel utterly connected to the grand passions, the thrilling patriotism and the intense devotion and sacrifice of the Civil War. At those times, it’s not play-acting, they say. It’s channeling.

A deadly decision

It was getting to be the evening of July 2, 1863. The First Minnesota, after being shifted about a half-mile south towards the left of the Union line, was still on Cemetery Ridge.

Col. Colvill, released from arrest in order to take charge of the regiment during the coming battle, was back in command. They had waited and watched all day, held in reserve. Now, in front of the Minnesotans, the Federal III Corps was coming apart, panicking and retreating under an attack by two brigades of Alabamans.

The demoralized Northern troops were running for cover – “skedaddling,” they called it in those days – running right through the Minnesotans, who tried without success to make them stand their ground. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, one of the best generals the Union had to offer, sized up the situation and realized in an instant that desperate measures were needed to stem the Confederate advance long enough to bring up fresh Union troops and prevent disaster.

The only troops at hand were those of the shrunken First Minnesota. There were just 262 of them on hand. Another 60 or so had been detached to other positions earlier in the day.

“Charge those lines,” Hancock ordered, pointing down the slope, where 1,600 Confederate soldiers – seven times the number of Minnesotans in front of Hancock – were now racing forward.

Colvill, released from arrest only hours before, stepped in front of his men, knowing what was being requested of them. He asked if they would go with him. They answered yes.

“Every man realized in an instant what that order meant,” Lt. William Lochren would write later. “Death or wounds to us all; the sacrifice of the regiment to gain a few minutes’ time and save the position, and probably the battlefield. And every man saw and accepted the necessity for the sacrifice.”

The time machine

Wool uniforms are tortuously uncomfortable in the heat. Spectators pester re-enactors with stupid questions, gibes, and requests to play with their rifles.

The muzzle-loading rifles are not toys. They are real weapons, re-creations as deadly as the originals but heavier (about 10 pounds instead of the original nine).

The barrels have been beefed up to lessen the chance they will explode, injuring re-enactors and leading to – this is the 1990s, after all – litigation.

Put a middle-aged, overweight modern American in a wool uniform on a hot day and make him tote a 10-pound gun across a smoke-filled, adrenalin-pumping battlefield and you can see why re-enactment organizers urge the unfit to stay away. Last year, at a re-enactment of the Antietam battle, a man died.

Despite the hazards and the discomforts – or maybe because of them – re-enactors say they learn more about the bygone era of the Civil War in mock battles and in the campgrounds around them than they could in books.

“It’s like a time machine,” says Dave Arneson, a former re-enactor with the First Minnesota who now coordinates re-enacting for the Civil War Center at Louisiana State University.

“No matter how much you may have read about it, being lost in the middle of 10,000 men seems impossible until it happens to you,” says Arneson. “There you are, in a battle, 10 to 20 feet apart, and you are all alone. Spooky.”

Stepping toward fate

The instant after Colvill asked his men if they would join him, the First Minnesota was on the move, down a gentle slope, heading for a dry creek 200 yards to the west roiling with rebels.

The weeks of marching, the hours of waiting, the hardships, the lost comrades, the battles of the previous two years – it had all come to this moment. The war was on the line at Gettysburg .

It was most definitely on the line here, where the Minnesotans, bayonets at the ready, were being thrown in the path of the enemy.

”The regiment, in perfect line, with arms at ‘right shoulder, shift,’ was sweeping down the slope directly upon the enemy’s center,” Lochren recalled. “No hesitation, no stopping to fire, though the men fell fast at every stride before the whole concentrated fire of the whole Confederate force.” Men dropped and fell, brought down by rifle fire and artillery. Their comrades closed the ranks, stepping over the fallen men.

“The bullets were coming like hailstones, and whittling our boys like grain before the sickle,” Sgt. Plummer would recall. “It seemed as if every step was over some fallen comrade,” Lochren wrote. “Yet no man wavers, every gap is closed up … the boys … with silent, desperate determination, step firmly forward in unbroken line.”

“Every faculty was absorbed in the one thought of whipping the enemy,” an anonymous “Sergeant” wrote later, telling his story in the Pioneer Press. “We fire away three, four, five irregular volleys … the enemy seemed to sink into the ground.”

We advanced down the slope till we neared the ravine, and ‘Charge!’ rang along the line, and with a rush and a yell we went. Bullets whistled past us, shells screeched over us, canister and grape fell about us. Comrade after comrade dropped from the ranks, but on the line went. No one took a second look at his fallen companion. We had no time to weep.

- Sgt. Alfred P. Carpenter

The Insignia of the First Minnesota

The First Minnesota rushed through the storm of bullets – with nothing but death to look for, and no hope or chance for any other success than to gain the brief time needed to save that battlefield. And not a man wavered.

Lt. William Lochren, First Minnesota Volunteers

William Colvill

William Colvill, commander of the First Minnesota at Gettysburg, was grievously wounded and carried from the field. Years later, in 1905, still bearing his scars, he was scheduled to lead a parade of Civil War veterans to the new Minnesota State Capitol built as a monument to the valor of the Union soldiers. Colvill died in his sleep the night before the parade: Instead of leading it, his body was laid in state in the Rotunda of the Capitol. His larger-than-life statue still looks over the Rotunda today.

William Colvill, commander of the First Minnesota at Gettysburg, was grievously wounded and carried from the field. Years later, in 1905, still bearing his scars, he was scheduled to lead a parade of Civil War veterans to the new Minnesota State Capitol built as a monument to the valor of the Union soldiers. Colvill died in his sleep the night before the parade: Instead of leading it, his body was laid in state in the Rotunda of the Capitol. His larger-than-life statue still looks over the Rotunda today.

The sun had gone down and in the darkness we hurried, stumbled over the field in search of our fallen companions, and when the living were cared for, laid ourselves down on the ground to gain a little rest, for the morrow bid fair for more stern and bloody work, the living sleeping side by side with the dead. Thousands had fallen, and on the morrow, they would be followed to their long home by thousands more.

Sgt. Alfred Carpenter

Part 3

A Regiment Counts Its Losses

The rushing Minnesotans made a thin blue line, barely 100 yards from one end to the other, rolling toward the Confederates. The Rebels, 1,600 Alabamans who up to now had been chasing skedaddling Yanks, suddenly faced a row of bayonets coming at them like a scythe.

They stopped in their tracks, stunned at the sight. Surely there must be thousands more Yankee troops hidden in the smoke and haze behind this pathetically small number of men moving steadily toward them. It would be madness for fewer than 300 men to try to stop the swarms of Confederates.

There were no other Yankees – only these 262 men of the First Minnesota, a sliver of a once-brawny regiment from the western frontier of the Union. Unless they somehow broke the Confederate attack, buying time for Union commanders to hurry more troops to the scene, the Rebels would stream through the center of the Union lines, roll up the flanks, and drive the Union Army of the Potomac back to Washington.

The only men among the 90,000 federal troops at Gettysburg who came from west of the Mississippi, the Minnesotans represented just a tiny fraction of the blue uniforms on the field, about one-third of one percent of the Union troops. Now fate – and self-sacrifice – would turn that tiny fraction into a potent, tide-turning force. Minnesotans would absorb the full force of the Confederate attack, buying time with their blood.

I wanted to see it

A white van with Illinois license plates pulls to the side of the Park Service road across from the monument to the First Minnesota at the Gettysburg National Military Park.

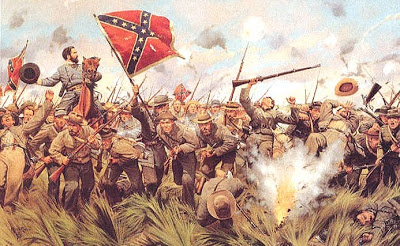

Seven loud, laughing men jump out, buttoning blue wool jackets and placing replica Union forage caps on their heads. Approaching a Park Service marker next to the Minnesota monument, the men suddenly become quiet. Before them is a copy of a painting by Rufus Zugbaum – the original is in the governor’s reception room in the Minnesota State Capitol – showing the First Minnesota’s fateful fight on July 2, 1863.

Their leader – the only somber one in the bunch – is an 18-year-old Civil War re-enactor from Glenview, Ill., who insisted his companions (all older) stop at the Minnesota monument. On a battlefield dotted with hundreds of monuments, the First Minnesota’s handsome statue of a running rifleman is often overlooked by battlefield tourists. But to many who have studied the pivotal battle that occurred here 135 years ago, the monument marks a place of special importance.

“I told you so,” young Tim Blackwelder says reprovingly. “See – the First Minnesota lost 82 percent. That kind of sacrifice is just incredible. It’s not as talked about as much as what some other regiments did. But it’s the most important thing that happened here, and I wanted to see it.”

“Awesome,” says one of the others.

The group is quiet now, all easy chatter at an end. The men, in their blue uniforms, which smell as if they have been worn a long time, peer reverently toward the west, where the sun is beginning to set, its golden rays slanting through the haze of a hot summer’s evening in Gettysburg .

Toward that setting sun, 135 years ago, charged the First Minnesota.

Two implacable foes

“The men were never made who will stand against leveled bayonets coming at them with such momentum and evident desperation,” Sgt. William Lochren would write after the battle.

As the Minnesotans came at them, the first line of Rebel soldiers broke and retreated through the ranks of the line behind them. The whole Confederate advance began to grind to a halt, letting Rebel riflemen and artillery try to keep those bayonets at bay. Alone in front of thousands of Confederates, the Minnesotans were easy prey.

More than 100 of the Minnesotans had fallen, dead or wounded, before the regiment even fired its first volley. Now, the survivors had reached the empty bed of Plum Run, taking cover behind rocks and bushes, trying to hold off the Rebels. The Confederate advance had stalled, and Union reinforcements were on the way. But for an agonizing eternity that was probably only about an hour, the remaining Minnesotans struggled to stay alive.

Many of the survivors would remark later that the Alabamans they had faced fought with equal courage. There had been 1,700 Alabamans in the attack. By the end of the day, after overwhelming other Union regiments, then being halted by the First Minnesota, there were only about 1,000 left. It’s doubtful that two more implacable, or worthy, foes met anywhere in the Civil War.

“There is no mistake but what some of those Rebs were just as brave as it is possible for human beings to be,” Sgt. John Plummer wrote. From a Civil War soldier, there might be no higher compliment.

Dusk began to turn toward darkness. Regiments of New Yorkers began to take the field near the Minnesotans, firming up the position and allowing the battered remnant of the First Minnesota to withdraw at last. Some of the Minnesotans still didn’t want to leave. They didn’t want to back down.

The regiment’s commander, Col. William Colvill, had been severely wounded by an exploding shell (“Then came a shock like a sledge-hammer” is how he would describe it later) and lay in a slight hollow, hugging the ground and listening to bullets whizzing past.

Three other officers had also fallen, leaving the remains of the regiment under the command of Capt. Nathan Messick. Three color bearers had fallen, but each time another soldier picked up the battle flag of the First Minnesota and carried it forward.

It may only have been nightfall that prevented the unit’s elimination. The long day – started when the First Minnesota was wakened before dawn and moved to the battlefield, where it had stood and waited all day before being thrown into battle at dusk – was finally over.

The Union position had been saved. The Union army would survive to fight a third, decisive, day at Gettysburg . But the First Minnesota was a shadow of what it had been that morning.

“The bloodied field was in our possession, but at what a cost,” Sgt. Alfred Carpenter wrote. “The ground was strewed with dead and dying, whose groans and prayers and cries for help and water rent the air.”

Richard Moe, author of “The Last Full Measure: The Life and Death of the First Minnesota Volunteers,” sums up the situation as darkness fell: “For the Minnesotans, the fighting of July 2 was over, but not the dying.”

On Thursday, the anniversary of the First Minnesota’s charge, a steady stream of visitors stopped at the regiment’s monument to pay homage and to contemplate the meaning of that sacrifice in their own lives.

Watching the visitors come and go is almost like watching people come into church. Without a doubt, this is a holy place. There are ghosts on this battlefield.

“We want to be here – on the anniversary – at the exact same moment they made their charge,” says Robert Niemela, an English teacher at Harding High School in St. Paul. “We want to feel what it’s like: how it looks, the time of day, the location. The experience.”

Niemela and three other Harding teachers – Bob Wicklem, Ron Knox and Will Williams – are sitting in the shade at the base of the Minnesota monument, waiting for the sun to lower in the sky, waiting to wade through the hip-high grass covering the field where the First Minnesota made its charge. At home in St. Paul, they belong to a Civil War roundtable that meets regularly to discuss the war and its meaning. Here, at Gettysburg, they feel humbled.

“I just get a bit of a feeling of awe,” says Williams, whose great-grandfather was in the Second Minnesota Regiment. “Being here gives me a sense that, in some way, I’m there … back then. I feel a strong connection.”

“The math teachers in our group figured out that there’s been more than 48,000 days since the First Minnesota made its charge,” Niemela says. “And in all that time, I don’t think there’s been a day that’s gone by that someone hasn’t stopped here to marvel at what they did.”

‘Where is Isaac?’

Struggling in the dark to help the wounded off the field, Sgt. Henry Taylor – a school teacher who had left his job to enlist in the First Minnesota – could think of only one thing: What had happened to his brother, Isaac?

“I help our Colonel off the field but fail to find my brother who, I suppose, is killed,” Henry wrote in his journal. “I rejoin the regiment and lie down in the moonlight, rather sorrowful. Where is Isaac?”

Henry had looked for Isaac for more than an hour in the dark. Another soldier said he had seen Isaac near the end of the fight, while most of the others were withdrawing, still firing away at the Confederates. And smiling.

Early the next morning, Henry got the news he had feared. A soldier had found Isaac on the field; he takes Henry to the spot.

“I find my dear brother dead!” he wrote in his journal. “A shell struck him on the top of his head and passed out through his back, cutting his belt in two. The poor fellow did not know what hit him.”

Henry retrieved Isaac’s pocket watch for a keepsake, then wrapped his brother in the half-tent soldiers carried to shelter themselves. With the help of some comrades, he then buried his brother on the spot, putting up a board marked “I.L. Taylor, 1st Minn. Vols.” He wrote on it:

No useless coffin enclosed his breast,

Nor in sheet nor in shroud we bound him,

But he lay like a warrior taking his rest,

With his shelter tent around him.

“Isaac has not fallen in vain,” Taylor told his parents when he wrote to inform them of his brother’s death three days later. “What though one of your six soldiers has fallen on the altar of our country, ’tis a glorious death; better die free than live slaves.”

In another letter to his sister, Henry described the burial: “As we laid him down, I remarked, ‘Well, Isaac, all I can give you is a soldier’s grave’ … I was the only one to weep over his grave – his Father, Mother, brothers and sisters were all ignorant of his death.”

On the same side now

Another visitor stops to pay homage at the First Minnesota monument. This one is wearing a T-shirt with a Rebel battle flag on it. He turns out to be a soldier from Alabama – a real one.

“Major Kevin Gray,” he says, introducing himself with military efficiency. “First Battalion, 152nd Armor, Alabama National Guard.”

He tells me he has a special reason for visiting the Minnesota monument. Until now, his armored unit has been part of a separate brigade. But in its wisdom, the U.S. Army (the modern one) has decided in 1998 to assign his unit to the 34th Infantry Division.

God – and generals – must have a sense of humor. The 34th Infantry Division traces its lineage back to a heroic regiment of soldiers from a frontier state that earned fame and glory at Gettysburg: the First Minnesota.

“We’re all on the same side now,” Gray says, pointing across the field to where Alabamans and Minnesotans clashed 135 years ago. “Those guys over there – and you guys over here – we’re all in it together. I can’t wait ’til we go to field exercises against each other. We’ll see if we can’t break out a few Confederate flags and put ’em on our tanks. That ought to be interesting.”

The final 100

Finished burying their dead and removing their wounded to field hospitals, the men of the First Minnesota were moved about a third of a mile north and stationed along a fence in a line of approximately 9,000 Federal troops. Reunited with three companies of the regiment that had been detached for other duties the day before and thus had not taken part in the charge, they waited with the other exhausted Union soldiers.

Counting survivors of the charge – only 47 of the 262 men had escaped death or injury – there were barely 100 Minnesotans left on the field.

All was quiet until early afternoon. Then all hell broke loose.

Three hundred cannons opened up in the largest cannonade ever in this hemisphere. For two hours, the ground shook and men and horses died. Then, when the cannons fell temporarily quiet, 12,000 Confederate soldiers stepped out from among the trees along Seminary Ridge and headed straight at the Union lines a mile to the east, hunkered down along Cemetery Ridge.

It would go down in history as Pickett’s Charge. And once again, the First Minnesota would stand in the way.

Desperate Valor

In self-sacrificing desperate valor, this charge has no parallel in any war.

– From the inscription on the monument to the First Minnesota Volunteers at Gettysburg , erected by the people of Minnesota, 1897

The Diary Of Isaac Taylor

“Order from Gen. [John] Gibbon read to us in which he says this is to be the great battle of the war & that any soldier leaving ranks without leave will be instantly put to death,” Isaac Taylor wrote in his diary July 2, 1863. He was killed the next day in the battle of Gettysburg, and buried by his brother Patrick. Four other Taylor brothers also served in other Union regiments during the Civil War. Judson was in Company K of the Eleventh Illinois Cavalry when he died at Vicksburg on December 1, 1864. Brothers Jonathan (Second Minnesota Battery of Light Artillery), Danford (Twelfth Illinois Cavalry), and Samuel (102nd Illinois Infantry) all survived the war.

Part 4

Once again, the Minnesotans were in the line of fire.

July 3, 1863, a Friday, the day before Independence Day, started out hot and sultry. By 2 p.m., it was a sweltering hell in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. Along a rough-hewn timber fence, a band of bloodied Minnesotans pressed themselves as closely to the ground as possible – so close, one said later, that he could not breathe.

Overhead, the shot and shell of 300 cannons were flying, shuddering the ground and making it impossible to hear or even think. Except for the Union artillerymen, whose duty it was to stand and return the Confederates’ cannon fire, the Union lines waited and prayed.

“All other living things sought shelter from the terrible storm,” wrote Sgt. James Wright, a soldier who had left behind his studies at Hamline University in St. Paul to join the crusade against the Confederacy. “The scene brought before the imagination that great day when men shall call upon the mountains and the rocks to fall upon and hide them.”

After a while, however, the exhausted Minnesotans couldn’t help themselves: “As men will get accustomed to anything, before two hours of this cannonade had ended, some of the most weary were sleeping soundly,” recalled Lt. William Lochren.

Only 18 hours earlier, the Minnesotans had made a heroic charge that had stopped the Confederate Army from overrunning Union lines, possibly changing the outcome of the Civil War. But they had done so at an enormous cost, paying an almost inconceivable price by today’s standards. More than 200 of the First Minnesota Regiment’s 300 men were dead or wounded; the dead had been buried just that morning, laid to rest in rough graves dug by their comrades.

Now the 100 or so survivors were in the midst of the biggest cannonade in American history, praying to stay alive until its conclusion. Still, they knew when the cannons quieted that the awful Confederate charge must be in the offing, forming near the tree-line, a mile to the west, where Robert E. Lee’s Confederate Army of Northern Virginia was preparing an all-or-nothing gamble to win the war.

Incredibly, heroically, the day after being shattered in battle, the remaining Minnesotans would once again meet the challenge.

Feeling the ghosts

Forty blue-clad soldiers, a 34-star United States flag floating above their ranks, march deliberately through the tall grass, flushing whippoorwills and other ground birds from cover as they head down a slight slope towards a muddy creek named Plum Run. There is the steady beat of a drum as they go, eerily echoing along the creek. On the flag, fluttering over their heads, are the words First Minnesota Volunteers. The date is July 2 – but it’s not 1863, it’s 1998. When you let the Civil War get into your head, however, those two dates don’t seem far apart.

It’s not the First Minnesota that fought and died at Gettysburg that is marching now on the field of battle, surrounded not by rifle-toting Rebels but by video-camera-carrying tourists. It’s an apparition, a living-history impression of those Minnesotans of 135 years ago, respectfully performed by Civil War re-enactors from Minnesota.

They have just gotten off a bus after a 24-hour ride from the Twin Cities, in time to participate in the largest Civil War re-enactment ever staged and, more importantly, in time to honor their spiritual forebears on the anniversary day of the First Minnesota’s historic sacrifice. They have come to offer ritual and respect to the original First. To honor the memory of the dead and the legacy of its self-sacrifice. And to feel the ghosts of Gettysburg . So many come to honor these memories. One has left a letter at the base of the monument memorializing the First Minnesota Regiment at Gettysburg.

“Dearest Isaac,” the letter begins. “One hundred and thirty-five years ago today, you died here in order to preserve a nation and all its rights that I am fully aware and able to enjoy today.”

The letter to Isaac Taylor is wedged into the monument by two small desk flags – an American flag and a Minnesota flag – stuck into the ground. It was left there Thursday, the 135th anniversary of the First Minnesota’s charge, by a woman from Missouri who signed herself “Donna.”

It’s not unusual to find such letters near the monuments at Gettysburg. Like similar letters left at the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C., they are picked up and collected by the National Park Service. And like the Vietnam-era missives, they also speak of reconciliation and remembrance.

Isaac, who died near the end of the famous charge as his comrades withdrew from the field, left no descendants. Donna is the great-great-granddaughter of Isaac’s brother, P.H. (Henry) Taylor, who buried his 25-year-old brother on the field maybe 200 yards west of the monument, with the lament, “Well, Isaac, all I can give you is a soldier’s grave.”

Among those who care about the Civil War and the First Minnesota, the Taylors are icons, the epitome of the kind of men that made the regiment famous. And here on the anniversary, like a message from beyond, is a letter left by a hero’s descendant, a letter that poignantly echoes the past.

Driving through the lush, wooded hills southwest of Gettysburg this weekend, it feels like a crazy journey through time. Smoke from a thousand campfires blankets the hills, hanging in the haze, making travel even more perilous along the roads crawling with thousands and thousands of men clad in blue and more thousands and thousands in gray. At night, you can hardly see them until suddenly they appear in front of you, carrying rifles or, sometimes, Coca-Cola. No one wore fluorescent orange in the Civil War. Driving at night around a re-enactment scene is dangerous.

The re-enacted Gettysburg battle, which began Friday and concludes today with a full-scale re-enactment of Pickett’s Charge, is being held on a farm a few miles from the actual battlefield; the 20,000 re-enactors (up from an expected 15,000) and at least 35,000 spectators would utterly destroy the battlefield shrine maintained by the National Park Service.

But during the day, the real battlefield and the adjacent town of Gettysburg are saturated with blue and gray. Re-enactors carrying battle flags re-trace the steps of the regiments they now portray. Women in period hoopskirts stroll through the town, sometimes accompanied by children in shorts and Air Jordans, adding atmosphere.

Gettysburg’s stores, offering Civil War artifacts, T-shirts, high-priced art and bumper stickers (“If at first you don’t secede, try again,” reads a pro-Rebel one) are mobbed with souvenir hunters. But above and beyond all the hoopla seems to be a genuine sense that at Gettysburg something profound and meaningful occurred. Not just in the history books. In our lives.

Protecting the flag

Twelve thousand – some say it was 15,000 – Confederates were on the move. The artillery barrage had ended, momentarily. The Union line, some 9,000 Northerners dog-tired from two days of battle, waited in amazement as the Rebels stepped out across a mile of open field. Then the Union artillery went to work, cutting the Confederates to pieces. The slaughter was unprecedented, even for the Civil War.

By the time the advancing gray line reached the Union positions, it was slowing to a halt under a brutal hail of rifle shots. The First Minnesota, waiting along a fence in the middle of the line, might have sat this one out. After what it had been through the day before, no one might have minded. But Cpl. Henry O’Brien had other ideas.

O’Brien, from St. Paul, had picked up the First Minnesota’s battle flag when the color bearer had been shot through the hand in the first exchange of rifle fire between the Rebels and the Union line, the bullet shattering the flagstaff. Now O’Brien grabbed the flag and leaped over the fence, charging toward the oncoming Confederates. His comrades, as much to protect their colors as anything, followed.

Lt. Lochren was angry at first, blaming O’Brien for “imperiling” the regiment’s flag, stained in blood the day before. But the effect of O’Brien’s act “was electrical,” Lochren wrote later. “Every man of the First Minnesota sprang to protect its flag, and the rest rushed with them upon the enemy.” Charging headlong onto the field, the Minnesotans encountered the 28th Virginia Infantry Regiment and engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat.

“If men ever became devils, that was one of the times,” Lt. William Harmon recalled. “We were crazy with the excitement of the fight. We just rushed in like wild beasts. Men swore and cursed and struggled and fought, grappled in hand-to-hand fight, threw stones, clubbed their muskets, kicked, yelled and hurrahed!”

When it was over, 17 more Minnesotans had been killed or wounded; the dead included Capt. Nathan Messick, who had taken over command of the regiment when Colvill and all the regiment’s field officers had been wounded or killed the day before.

The Minnesotans also had captured the 28th Virginia’s battle flag. Marshall Sherman, a 37-year-old house painter from St. Paul who fought the last day at Gettysburg barefoot after his shoes had come apart, captured the flag. Both he and O’Brien, who had been wounded while carrying the First Minnesota’s flag, would later be awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for their actions that day.

Pickett’s Charge had been repulsed, the Confederate Army had been defeated, the three-day battle of Gettysburg was over, the fortunes of war had changed in the favor of the Union. For Minnesota, the price had been painfully high: Nearly 60 men were dead, another 170 wounded.

When the news of the martyred First Minnesota reached home, it would cause great sorrow. Later, it would inspire pride. The state of Minnesota would eventually neglect but never forget what its sons had done at Gettysburg .

A time to weep

Led by Capt. Keith Gulsvig, a computer programmer from Champlin, the re-created First Minnesota marches into a woods along the creek where the 215 men of the regiment were killed or wounded on July 2, 1863.

Gulsvig sends forward scouts to search for some special boulders: Behind these rocks, the men of the First Minnesota sheltered from Confederate fire in 1863. But the woods weren’t here then, and the ground has become sedimented, making the rocks harder to find.

At last, they are discovered and the 40 Minnesota re-enactors move forward to place miniature U.S. and Minnesota flags by the stones. Gulsvig takes his canteen, full of water from Fort Snelling, where the First Minnesota trained before going to war in 1861. Pouring a swallow of Minnesota water into the out-stretched cup of each re-enactor, Gulsvig pours the remainder on the hallowed ground and proposes a toast: “To the First Minnesota!”

“To the First!” his comrades chime.

Paul Molina, a video producer and re-enactor from St. Paul, offers a prayer: “Lord, we thank You for letting us travel safely here to Gettysburg and we thank You for the incredible sacrifice the First Minnesota made. God bless all of those who served their country here, both blue and gray. And help us put on an impression worthy of The First for all of the people who have come to see us this weekend. Amen.”

`”Three cheers and a `tiger,” someone calls.

“Huzzah! Huzzah! Huzzah!” they shout, their voices echoing in the leafy woods.

Then, in an imitation of the ferocious growl that Union troops liked to do, they `”grrr-grrr” like tigers and start to head back across the famous field towards the Minnesota monument and their bus.

I tell Gulsvig about the letter Donna left at the monument. And I begin to read from the copy I jotted down in my notebook. Others come to gather and listen to Donna’s words to Isaac Taylor, hero of Gettysburg, slain and buried temporarily somewhere near where we are standing:

“Your legend has lived on through your brother. The story was told to me by my grandmother, Alice Deane Taylor Davis, Henry’s granddaughter. I have also visited your permanent grave.” (Isaac Taylor is buried in the Gettysburg National Cemetery, where President Abraham Lincoln said the dead had `”given the last full measure of devotion,” about two-thirds of a mile north of where he was buried by his brother on the morning after the charge.)

“Your bones may be there but your blood is in the ground here where you fell,” Donna’s letter continues, `”mixed in with the other brave men who were killed. I placed a Minnesota state flag on your grave … It is a humbling experience coming here where you were killed. …

“Rest peacefully, my uncle, as your mission has continued and our United States of America remains United! `

“With great admiration, Donna.”

I finish reading the letter and look up. The men of the re-constituted First Minnesota are crying. One hundred and thirty-five years after the battle, Minnesotans finally have time to weep at Gettysburg.

1st Sgt. James Wright

“All other living things sought shelter from the terrible storm,” wrote Sgt. James Wright, a soldier who had left behind his studies at Hamline University in St. Paul to join the crusade against the Confederacy. “The scene brought before the imagination that great day when men shall call upon the mountains and the rocks to fall upon and hide them.”

Trying On A Legend

Part 5

Their Proudest Boast

Rain fell on Gettysburg on the Fourth of July 1863, covering the hushed fields and forests in mist as the survivors of the First Minnesota Volunteers, for the second day in a row, buried their slain.

For the first time in three days, the Minnesotans would have time – and appetite – to eat. And they would eat well this Independence Day: When the regiment’s rations arrived, there would be enough for 300 men. But there weren’t 300 men in the First Minnesota any longer. Barely 100 of the 330 men who had marched to Gettysburg had escaped being killed or wounded.

Although the regiment would take part in other battles after Gettysburg – and serve with distinction in those – the war would soon be over for the First Minnesota. The regiment’s three-year enlistment was set to expire in April 1864.

All told, more than 1,400 Minnesotans had served in the regiment, including replacements sent East to fill the ranks after earlier battles. Of that number, more than 200 had been killed, dozens more had died of sickness, and at least 500 had been wounded, many scarred for life.

Posted to New York City for a short time, the regiment paraded through Brooklyn and was observed by a woman who had happened to be in Minnesota three years earlier when the First Minnesota – full of enthusiasm and at full strength – marched off to war. She was shocked by how the men had changed.

“As I saw this little fragment of the once splendid Minnesota First march by me, carrying their stained and tattered flag … I absolutely shivered with emotion,” the anonymous “Lady” wrote in a letter published in the St. Paul Pioneer. “There the brave fellows stood, a grand shadow of the regiment which Fort Snelling knew. Their bronzed faces looked so composed and serious. There was a history written on every one of them. I never felt so much like falling down and doing reverence to any living men.”

She wasn’t alone in her adulation of the regiment. In February, the First Minnesota was honored at a grand feast in Washington, D.C., an event attended by Vice President Hannibal Hamlin and a host of Washington’s leading figures who fed the Minnesotans sumptuously and toasted them endlessly. At the head tables were the regiment’s banners and its ailing commander, Col. William Colvill, who was still recuperating from wounds suffered at Gettysburg and who had to be carried by the men into the hall.

It was time to go home.

What we were like

“Absolutely amazing.”

I watch and listen as Richard McMurry talks to himself at the monument marking the spot where the First Minnesota made its charge on July 2, 1863, losing 82 percent of its men.

McMurry, a bearded Texan who now owns a machine shop in Washington, looks and sounds like Shelby Foote, the Southern Civil War historian whose drawling anecdotes helped make Ken Burns’ public television series about the Civil War a hit.

McMurry is a Civil War re-enactor who is wearing a rumpled and sweaty gray uniform and a gray Rebel cap with a star on the top that has “Texas” stamped on it. Like many others, he has come as a pilgrim to the battlefield and has stopped to pay his respects to Minnesota.

“The First Minnesota has ALL the elements,” he says loudly, as if he is speaking to an audience as he runs his fingers along the marker that tells the story of the regiment’s loss. “It’s absolutely glorious! It has everything: Honor … valor … the nick-of-time thing … heroism … the gallant commander, leading his boys in …

“Those things are everywhere on this battlefield. But the First Minnesota has it all. … That’s what makes it so awe-inspiring. … Elementary schools ought to have a full course on the gallantry of the Civil War soldier. … This is a cross-section of America, here! To be able to do what these boys did. … think what that says about America! It shows what we were like then. I think we have lost a lot of it since.”

The re-enactors have done a masterful job of transporting us back to that time: The wooded hill is wreathed in a great pall of gray clouds that rolls onto the field where countless thousands of men, mere shadows in the smoke, move toward battle.

Suddenly, a half-mile line of artillery opens up, scores of cannons go off in a thundering ripple that stretches beyond vision on the far side of the field. From every direction, the ripping sound of rifle volleys echo, horses whirl as their riders spur them to the action, and the sound of bugles, fifes and drums carries on the acrid air.

Then the noisy, gas-powered generator at the Sno-Cone booth behind me starts up again, drowning out the sound of the bugles. Oh, well. The action has stopped momentarily anyway because another Confederate has fallen off his horse and an ambulance – a modern one with internal-combustion engine and flashing lights – is making its way onto the field.

The 135th anniversary of the battle of Gettysburg brought as many as 30,000 Civil War re-enactors – twice the expected number – to the hallowed shrine over the Fourth of July weekend. The result was a stunning display of Civil War firepower and tactics. And a three-hour bumper-to-bumper drive to traverse the five miles from town to the re-enactment site.

It was worth it. The battle is fierce and spectacular. In an hour-and-a-half, a million shots might have been fired. Without effect, of course, other than a smattering of re-enactors who got tired or ran out of ammunition and decided to “take a hit,” pretending they were shot and falling over to rest a spell. No one was shot for real, but some re-enactors did “see the elephant” – soldier’s slang for the gut-churning experience of seeing battle up close for the first time, even if it’s only a mock battle.

Tom Stodola, a die-caster from Shoreview who is a re-enactor with the First Minnesota Volunteers, had the misfortune to “shoot” a Rebel at such close range Saturday that the Reb clunked him in the ankle with his rifle as he fell, causing Stodola to fall himself. As he toppled over, Stodola hit his right eyebrow on the hammer of his rifle. Result: seven stitches and a shiner.

“I got my red badge of courage,” Stodola winces back at his tent, in the woods where the First Minnesota is ensconced in the middle of a mile-long Civil War-era encampment inhabited by countless thousands of rank-smelling re-enactors, flushed from a day of battle and looking a bit worse for wear. “That’s the cloest I ever want to come to war.”

One of Stodola’s fellow re-enactors is a 24-year-old Minneapolis office worker, a woman whose last name is Elbert but who doesn’t use her given name while re-enacting (I’ve agreed not to use it here). Instead, she goes by the name Thomas, and does her best to pass as a 17-year-old Union soldier boy.

Pvt. Thomas Elbert is not alone; there is one other woman in the reconstituted First Minnesota, and if you looked VERY closely, you could pick out a few others on the battlefield, including canoneers and cavalrymen. This isn’t a ’90s phenomenon. It’s a ’60s thing. The 1860s.

As many as 1,000 women served in the Civil War, passing as men, fighting in battles and dying for their country. After Pickett’s Charge on the last day at Gettysburg , to pick an example, one of the dead Confederates turned out to be a women. For Pvt. Elbert, her service as a re-enector is a tribute to the women who served back then – and the men, too.

“Yeah, I saw the elephant,” says Elbert, who at 5-foot-4, 117 pounds, is often referred to in the regiment as “the short skinny guy.” “I saw it, and it sat on me. It was dusty, I have hay fever, I couldn’t breathe. I crashed after the battle. My legs decided they didn’t want to work anymore.”

Still, she says, the exhaustion, the dirt and grime, the $800 she has spent on her rifle, uniform and gear – it’s all worth it to be at Gettysburg .

“I try to imagine what the original First went through, because we (th 40 or so Minnesota re-enactors) are a small group, like the First Minnesota was in 1863. When you know all of the people, and you think of leaving msot of them on the field … it’s frightening. And it’s frightening when the enemy comes close and they’re shooting at you and there’s just no way they could miss if they were shooting real bullets. It makes you think.”

According to DeAnne Blanton, an expert on women soldiers in the Civil War, women fought for the same reasons men did: patriotism, adventure, love (some disguised themselves as men so that they could go to war with their soldier husbands). “The women combatants of 1861 to 1865 were not just ahead of their time,” Blanton has written. “They were ahead of OUR time.”

Pvt. Thomas Elbert agrees: “It burns me up that people don’t know the history of women fighting in the Civil War. Don’t they think women can be patriotic, too? Women joined for the exact same reasons as men: for adventure, for money, for patriotism, to abolish slavery, to fight for a way of life, to get away from home.”

Adventure, patriotism, ending slavery. Why did the soldiers of the First Minesota do what they did at Gettysbrug – and many other places – in the Civil War? How should we regard the sacrifice they made? How should we think of them?

“What caused most of them to endure all this was duty, although few actually used the word,” wrote Richard Moe in his book on the regiment, “The Last Full Measure: The Life and Death of the Minnesota Volunteers.”

“They questioned their superiors and virtually everything else in the army at one time or another, but they never questioned the need to win the war. These were ordinary men, without pretense or guile, who happened to live at a time that was anything but ordinary. They had the same human shortcomings as any other group of men, but they also had an inner strength – perhaps stmming in part from life on the frontier – that helped them survive their incredible ordeal.”

James J. Hill, the St. Paul railroad tycoon, who would host many reunions for the survivors of the First in their later years, put it more succinctly: “They saw things straight.”

A hero’s welcome

Less than 20 percent of the original First Minnesota remained in the ranks when the regiment returned home in February 1864, traveling by train to La Crosse, Wis., where the rail lines ended, and finishing the journey by traveling in horse-drawn sleighs along the ice of the frozen Mississippi to St. Paul.

As the regiment neared the city, an artillery salute welcomed it, the cannons reverberating through the frozen valley with echoes of three years of valor.

Thousands came out to greet them in the cold, to weep with joy and with sadness, to touch them and to take talismans of their heroisms: Within a few years, co many Minnesotans had pulled a tiny thread from the Stars-and-Stripes the First Minnesota had carried at Gettysburg that only a few scraps were left, still hanging from the shattered shaft.

“Your banners are torn and tattered but have never been dishonored,” Gov. Stephen Miller, a former colonel of the regiment, would tell them.

On April 28, 1864, the third anniversary of their enlistment, and with Colvill still unable to walk, listening from a nearby carriage, the First Minnesota was mustered out of service at Fort Snelling. Many of the soldiers re-enlisted, forming the corps of the new First Minnesota Infantry Volunteers. Others went home, their soldiering done. The First Minnesota, its service to the Union immortalized by the deeds of Gettysburg, was history.

“Every member justly regards his own connection with the regiment as the highest honor of his life,” Lt. William Lochren, the regiment’s historian (who became a state senator and judge), wrote years later. “May our state always send forth such regiments whenever its safety, or the safety or honor of our beloved country, shall call its sons to arms.”

“Officers and soldiers of the First Minnesota Regiment, heroes of more than 20 battles,” Lt. Col. Charles Adams said at the mustering-out ceremony. “Never again will you all assemble until the reveille at the dawning of eternity’s morning shall summon us from the slumber of the grave. …May a merciful Providence direct you and crown you here with earth’s brightest honors. But however brilliant may be your future, your proudest boast will ever be, `I belonged to the First Minnesota.’

“Farewell.”

Terrible Slaughter In The First Minnesota. Less Than One Hundred Men And Officers Left All The Field Officers Wounded Four Captains Reported Dead.

Headlines in The Saint Paul Pioneer, July 9, 1863As I saw this little fragment of the once splendid Minnesota First march by me, carrying their stained and tattered flag … I absolutely shivered with emotion. There the brave fellows stood, a grand shadow of the regiment which Fort Snelling knew. Their bronzed faces looked so composed and serious. There was a history written on every one of them. I never felt so much like falling down and doing reverence to any living men.

Unsigned letter to the editor, St. Paul Pioneer

What's Left Of The Flag

Left Behind

Marshall Sherman

Marshall Sherman, a St. Paul soldier in the First Minnesota, won the Medal of Honor for capturing this Confederate flag at Gettysburg. Minnesota still has it and won’t give it back.

Pickett's Charge

The War Between Two States

Almost 135 years ago – that would be six score and 15, if you’re counting the Abe Lincoln way – a small band of battle-weary Minnesotans hurled themselves against a last-ditch onslaught of Confederates at Gettysburg .

The date was July 3, 1863, and that doomed rebel attack has gone down in history as Pickett’s Charge. The remnant of the First Minnesota Regiment, which helped repulse it – survivors of an encounter the previous day that killed or wounded about 80 percent of the Minnesotans ordered to stop a rebel charge – wound up in hand-to-hand combat with Virginia rebels. When the battle was over, Gen. Robert E. Lee’s Confederate army had been routed and the Minnesotans had earned undying fame capturing a Confederate flag.

The smoke has long since cleared from Gettysburg . But the tussle over the flag of the 28th Virginia Infantry Regiment isn’t over. Not by a long rifle shot.

A group of Civil War history re-enactors from Roanoke, Va., has asked the Minnesota Historical Society to return the blood-soaked, bullet-pocked battle flag to its native soil. The request has forced the Historical Society to turn to the Minnesota attorney general’s office for legal advice. It also has sparked strong emotions on both sides of the Mason-Dixon line, revealing the lingering wounds of a war that may be long ago but is hardly forgotten.

“Blood has been shed for that flag,” said Stephen Osman, site manager of the Historical Society’s Fort Snelling, which is holding its annual Civil War Weekend this Saturday and Sunday, one of several upcoming events to commemorate Minnesota’s role at Gettysburg on the 135th anniversary of the battle.

“Minnesotans gave their life blood for it,” said Osman, who also is a Civil War re-enactor in the First Minnesota Regiment, a nonprofit group that portrays the Minnesota soldiers who fought at Gettysburg . “Who are we to return it? That flag is a symbol of our putting that rebellion to an end. And it would be a disservice to the men who fought for it to give it back.”

Despite those deep feelings, the request for return of the flag may depend more on how the laws are interpreted than how feelings are gauged. The Virginians who are demanding the return of the flag – re-enactors who portray the 28th Virginia Regiment defeated by the First Minnesota at Gettysburg – say the law is on their side.

“Sure, a lot of blood was lost over this thing,” said Chris Caveness, a re-enactor in the 28th Virginia who heads the effort to get the Minnesota Historical Society to return the flag. “But the guns have quit and the pieces fit – all 50 states. They were a tough bunch, they were a great bunch, the First Minnesota,” said Caveness, an insurance agent in Roanoke, Va., who has a painting of the First Minnesota at Gettysburg hanging in his office. “But the war is over and we’re all Americans and it’s time to give the flag back.”

The Virginians want the flag turned over to a museum in Salem, Va., in the area where the 28th Virginia, also known as the Craig Mountain Boys, were mustered. They say that returning the flag would help bring “a reconciliatory close to this final chapter of a tragic time in American history.” The Virginians say they’d prefer to keep their efforts out of a courtroom. But they have made it clear they believe the Congress of the United States is on the Rebel side in this conflict.

In 1905, Congress passed a resolution ordering the War Department to return all flags in its possession from the Civil War. The Virginians say the flag of the 28th Virginia, captured at Gettysburg , was supposed to have been included. But the flag had gone missing. It wasn’t in Washington; it was back in Minnesota. Thereby hangs the tale.

The flag was captured by a barefoot Minnesota soldier, Marshall Sherman of St. Paul, who was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for his heroics. Sherman, according to an account of his deeds published in the Pioneer Press in 1893, confronted a Confederate flag bearer on the field, amid the smoke and confusion of a fight that had become so desperate many of the combatants, having run out of ammunition, were reduced to throwing rocks and clubbing each other with their empty rifles.

“ `Throw down that flag, or I’ll run you through,’ shouted Sherman,” according to the newspaper account, which reported Sherman used his bayonet to menace the rebel. After Sherman repeated his command to make himself heard above the din, “down went the flag and Sherman picked it up.”

Sherman, who would lose a leg in a later battle, carried the flag with him until he returned to St. Paul. For years it was on display at the old State Capitol, used to bind together the staffs of several of the First Minnesota’s flags that were displayed in a glass case. “And there it will remain until time shall have done its work and the colors borne by the Minnesotians (sic) in the civil war shall have crumbled into dust,” said the newspaper.

Not quite.

At some point, the flag was sent to the War Department in Washington, D.C., where it was catalogued and stored with scores of other Confederate flags taken by Union troops. At a later, unknown date, Sherman apparently “borrowed” the flag he had captured. When he died in 1896 it was still in his possession, and his will asked that it be burned. Instead, it eventually ended up in the Historical Society, where it last was displayed in 1963, for the battle’s centennial. Two years earlier, the Society had refused a request by the Virginia Historical Society to return the flag to Virginia, the last such request until now.

Russell Fridley, the society’s director in 1961, said Minnesota’s Historical Society did not wish “to use the flag to glorify Minnesota’s participation in the Civil War at the expense of Virginia’s.” But the flag, he said, was “one of the most tangible reminders” of Minnesota’s participation in the battle of Gettysburg and was of more historical value to the North Star State than to the Old Dominion.

Things look different down South.

“They stole our flag,” Caveness has declared flatly. “Marshall Sherman was a hero, brave and courageous, and he was entitled to the Medal of Honor he got. But he wasn’t entitled to keep the flag. There was more than just Marshall Sherman standing on that field. We’re all Americans. I know that if we had the Minnesota flag that there might be a part of my heart that said, `Our boys fought for this and we’d like to keep it.’ But I also know that giving it back would be the right thing to do.”

Minnesotans, however, are not likely to see the flag as “stolen.” To those who honor the history of the First Minnesota, the flag is a near-sacred emblem of Civil War sacrifice.

The flag is made of red wool in the “Army of Northern Virginia” pattern. It has the words “28th. Va. Inf’y” painted on it in white. Rebecca Rose, flag curator at the Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, Va., which has more than 500 Confederate flags in its collection, calls Minnesota’s rebel trophy “a very beautiful, very significant flag.”

The Museum of the Confederacy is not part of the effort to have the flag returned, and Rose said she is confident the flag is being properly preserved in Minnesota. But there’s something about Civil War flags, she said, that just gets people stirred up. They aren’t just flags. They are icons of holy causes – noble and tragic, victorious and lost.

Whether it is returned to Virginia will depend largely on the recommendation of Minnesota Attorney General Hubert Humphrey III, whose office is studying Virginia’s request. If the law is on the side of Virginia, Historical Society spokespeople say, the flag will go home.