April 1, 2013

Pioneer Press

By Nick Coleman

I was 30 years old, a journalist with a passing knowledge of Indian history. Yet it had never occurred to me, until I came across the name of Ernest Wabasha one day, that people still lived among us who were connected to the terrible events of 1862-63, the time of the so-called “Sioux Uprising” and the exile and banishment of the Dakota Sioux from their homeland. But there it was: The great-great grandson of Chief Wabasha was living on a reservation near Redwood Falls!

I looked up Mr. Wabasha’s telephone number and called to ask if I — a complete stranger — might visit some day. “What are you doing this afternoon,” he asked.

That was my first visit to a reservation, my first stroll through a cemetery with too many fresh graves, my first trip to a poor and neglected community in a state that had consigned its original people to the forgotten past. When I arrived at Mr. Wabasha’s door, I found a family party going on: Mr. Wabasha’s wife, Vernell, was celebrating her birthday. Maybe I should come back another day, I suggested.

“No,” Mr. Wabasha said. “It is good you are here.”

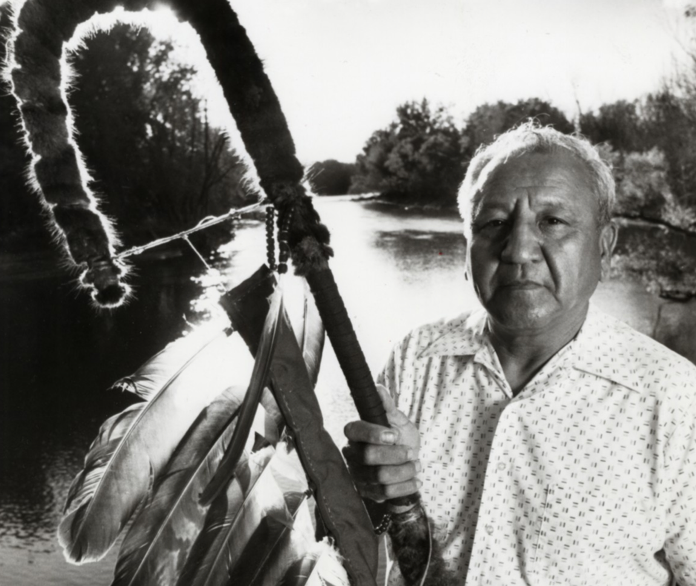

That was the start of a long friendship with a great man who died March 28, going home to the Spirit World at the age of 83. Ernest Wabasha would have been called chief of the Dakota if the U.S. still recognized hereditary tribal leaders. But even without official recognition, he was a true leader in a time of difficult transition for Minnesota’s native peoples as they emerged from the trauma of the past and invisibility in the eyes of the majority culture to take a proud place in society.

A Korean War veteran, a Honeywell engineer and a humble man of great dignity, he was one of the most ecumenical people I ever met, willing to explain to anyone how things had been and how they had become for Indians, without bitterness. In 1973, the year Time Magazine saluted “The Good Life in Minnesota,” Ernest and Vernell were denied a mortgage when they showed up to sign the loan — already approved — and the bank discovered that they were Indians. Undaunted, they moved to Lower Sioux, built a home on the reservation and started, quietly, to build understanding.

I saw Ernest and Vernell many times over the years. At the Mahkato Wacipi — the September Mankato Powwow — which Ernest gave his blessing to more than 40 years ago in a brave attempt to honor Dakota culture and traditions in the once-forbidden place where 38 Dakota men were hanged in 1862. I saw them at events promoting healing between the races, including the Great Dakota Gathering and Homecoming each summer in Winona, where a once-exiled and rejected people were welcomed back to the riverside prairie where Chief Wabasha’s village stood before the new state of Minnesota pushed it aside and shoved the Dakota to the brink.

On one memorable occasion, I saw Mr. Wabasha on the new Wabasha Bridge, presiding with his presence and his prayers for mankind. Once upon a time, there were many places in St. Paul where the Wabashas did not dare go. But in 1998, Ernest prayed for a future better than the past:

“I want to pray for the future,” he said in Dakota, his words translated into English. “That we all get along together and that we have understanding and respect for each other. I want to ask the Creator, the Grandfather, to help the people, to protect and guide us, to unite us all as human beings, to help us live in harmony and peace, and to live as brother and sisters.”

Mr. Wabasha’s prayer was printed in his funeral program the other day. I remember it every time I drive across the bridge that carries his name.

In 1987, I was privileged to be part of a groundbreaking yearlong effort by the Pioneer Press to tell the story of 1862 from an Indian perspective. I am proud of the work we did, which re-framed the history from an incomprehensible “uprising” to an all-too-understandable war that erupted as the Dakota faced elimination. We couldn’t have published our stories without Mr. Wabasha and his wife. And we wouldn’t have gotten them right.

I learned a lot during that year: Mr. Wabasha had the leg-irons that his great-great grandfather had worn during captivity. He also was the keeper of Chief Wabasha’s medicine bundle, a powerful sacred object that protected the people. But I almost wasted a full year learning facts about the Dakota War without understanding the most important thing about it.

Mr. Wabasha would teach me that, too.

Nineteen-eighty-seven was the 125th anniversary of the war and had been proclaimed The Year of Reconciliation by Gov. Rudy Perpich. In November, receiving a mysterious message that we should come to Lower Sioux one day, photographer Joe Rossi and I witnessed an extraordinary ceremony, a mass burial that finally opened my eyes to the underlying reality for the Dakota.

Boxes holding the bones of 31 Dakota who had died in a prison camp were lined up along a 70-foot-long trench that had been dug next to the little Episcopal mission on the reservation. The bones had been in a museum for more than a century and the boxes bore no names: Just labels indicating whether they had belonged to a man, or a woman, or even to a child. After prayers and songs in Dakota, Mr. Wabasha and the other men on hand began to sob heavily, taking shovels and filling the burial trench as tears streamed down their faces.

Rossi and I stood and watched, awestruck and overwhelmed by the emotions on display from events long ago. After a while, we put away our cameras and notebooks and took our own turns on the shovels, throwing dirt into a burial trench lined with sage, sweet grass and brokenness.

The U.S.-Dakota War is not a story in a dusty book. It is a wound in the hearts of a people.

Mr. Wabasha now rests in that same little churchyard, the task of reconciliation still uncompleted, but his work finished. He died only a few weeks before the 150th anniversary of the day his great-great grandfather and his people were forced onto boats at Fort Snelling and shipped down the Mississippi, past St. Paul and up the Missouri, to exile, starvation and endless punishment for the “crime” of being Dakota.

I am so grateful to have known Ernest Wabasha.

It is good that he was here.

Nick Coleman is a former columnist for The St. Paul Pioneer Press who is Executive Editor of The UpTake. You may reach him at nick.coleman@theuptake.org

A shorter version of this story was published by The Pioneer Press on April 1