Bards, wayfarers and conquerers have been singing the praises of this Portuguese city above the sea for centuries.

Poets, in my experience, do not make trustworthy tour guides. Their heads tend to be too high in the clouds, their hearts too full of feeling, to take note of the particulars of plumbing, traffic and ticket prices that concern your more pedestrian tourist types.

So it was with some skepticism that I read the poets’ blurb recommendations of Sintra, Portugal, printed in a local guidebook:

“Lo! Cintra’s glorious Eden intervenes/ In variegated maze of mount and glen,” quoth Lord Byron.

“Oh Sintra! Of legendary charm, princess sleeping in a wood of sorcery …,” enthused Oliva Guerra.

“Oh Sintra! Oh most welcome retreat where pain is forgotten …,” claimed Almeida Garrett.

Oh, puh-leese, I thought, dehydrated after the 11-hour flight to Lisbon, disillusioned by the urban sprawl that made my first hour of vacation look too much like 494 on Friday afternoon.

But after 30 minutes behind the wheel, in driving rain, dodging cars that gave no notice of their plans to change lanes, something almost magical started to happen. The highway narrowed into one winding lane, edged by wisteria and white-washed buildings. The rain stopped and the clouds parted as we coasted to a stop and stretched our legs on cobblestone sidewalks. Before us was a radiant white palace with two fairy tale chimneys. Above us, a lush green mountainside edged by the ruins of a Moorish castle.

“Oh Sintra!,” I could not help but sigh.

This sylvan city, set 1,736 feet above the Atlantic, has been having this effect on travelers for centuries. The Celts and the Romans believed Sintra’s mist-shrouded mountains emanated some magnetic spiritual force. The Muslims built their castle fortress here and the Hieronymite monks built a monastery. The Portuguese royal family moved the court here in the summer to escape the fevers and plagues of the city, and now budget travelers from all over the European Union travel by tram to enjoy five-star hotels and restaurants at two- and three-star prices.

Our visit started at the Tourism Office in Sintra’s central square. Back in the states, we had tried to reserve a room in one of Sintra’s famous quintas – noble estates where the king was once entitled to one-fifth of the land – but could find no vacancies online or by phone. But when we arrived at the tourism desk, we got our first lesson in Portuguese hospitality – nearly anything can be had if you make a polite attempt at “Bom dia” before you ask.

Soon, we were on a hazardous one-lane road – so tight we worried about our clinking side mirrors with oncoming cars. We turned in at the Quinta da Capela, once the 16th-century estate of the Duke de Cadaval, now a quiet and tasteful retreat. Two peacocks patrolled the immaculate grounds and though they tried to block our exit from the garden with an impressive display of their fanned tails, other attractions called.

Over the years, Sintra has known more than its share of madmen and philosophers. One was Sir Francis Cook, a 19th-century Englishman who built Monserrate, a fantastic Moor-inspired palace on the grounds of an abandoned garden – landscaped earlier by another eccentric Englishman named William Beckford. The overripe grounds contain 2500 species of exotic plants – towering California Sequoias, banyans and ferns and a ficus with roots that wind through a ruined chapel. In its day, a native novelist described the setting as a “trysting place, and beneath its romantic foliage noble ladies had surrendered to the arms of poets.” It casts the same spell today, as two teen-agers clutched one another and rolled down the green hillside, unconscious of the tour of British garden enthusiasts who watched.

Monserrate is certainly a monument to ego, but it is modest in comparison to the Palacio da Pena, built for Dom Fernando II, the so-called “artist” king. Architectural excess seems to have been a congenital problem for the Saxe Coburg-Gotha clan; Fernando was a cousin of Ludwig, Bavaria’s crazy castle king. This fabulous palace, on a high point of Sintra’s Serra mountainside, nods to nearly every period. It’s a complete mess, but fabulous because of the singular vision it took to create it. Fernando, who built the palace for his wife, (and a nearby Roman “ruin” for his mistress), died the year the project was completed.

Just below Pena stands the Castelo dos Mouros, built by the Muslims in the eighth century. Though the restoration of the dramatic embattlements was another pet project of Fernando II’s, he showed remarkable restraint, limiting his influence to landscaping and tuck-pointing, allowing the moss-covered stones to create their own mood. On the day we visited, a flutist stood near an ancient cistern and tried to match his musical greeting to the nationality of the tourists. Americans are so underrepresented that he played “God Save the Queen,” “Germany, Our Fatherland,” and “Bonnie,” before trying “Yankee Doodle Dandy.”

The tour guides say Sintra can be done in a day and that’s what we’d intended. But after a week of touring the southern half of Portugal, the rental car somehow missed every single exit to Lisbon and drew us back to Sintra instead. Pre-Christian astral cults claim the place has the same strange pull on them.

This time we stayed at Lawrence’s, the oldest hotel on the Iberian peninsula, where Lord Byron spent 10 days in 1809 working on “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimmage.” In 1989, a Dutch family bought the property – which had been abandoned for 35 years – and spent 10 years restoring the structure and arguing with the neighbors, who held up the liquor license. The 16-suite hotel reopened under its original name last year as a five-star affair with lovely antique furnishings, romantic verandas and always the faint sound of bell-clanging from the goats that graze the green slope below.

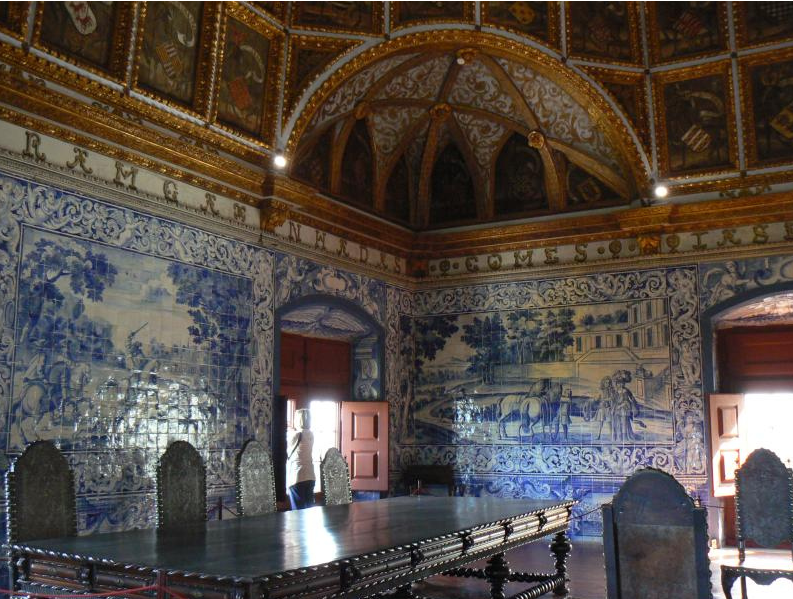

Politics have always been a favorite topic in this village, which radiates around the Palacio Nacional, or the Paco Real, the retreat that was a summer home to the royal family for almost 500 years. In the palace’s Sala dos Brasoes, a state room surrounded by Delft-like ceramic tiles known as azulejos, 74 of the most favored noble families are recognized with their own painted panels of stags. Though the palace has a distinctly fairy tale quality to it, it is full of evidence of the power struggles one expects t court. For instance, one king had a room – in which he is rumored to have trysted with a woman who was not the queen – painted with 136 magpies, a sharp insult to the gossipy ladies-in-waiting.

We ended our visit to Sintra with a seven-course supper in the candlelit dining room at Lawrence’s restaurant. There, we tasted sea bass and salmon, the traditional Portuguese pork and clams, duck confit, tuna pate, Port wine and a dessert of bananas flambe, prepared at our table by a sweet-faced concierge who had a flair for dramatics. It was a world-class meal and it took a deep breath before we could turn over the bill: It cost only $80.

Oh Sintra! Most welcome retreat where pain is forgotten … The poets were right about you.

For online reservations and tourist information, go to Virtual Portugal (www.virtualtourist.com/Europe/Portugal). It’s possible to reserve rooms at most of the famous quintas online, but most require a two- to three-night reservation, and may cost more than reservations made through the tourist office, located at Praca de Republica 23, (01-923 11 57).

A typical double room at the Quinta da Capela, (Estrada Velha de Colares, call 351-21-929-0170; fax 351-21-929-3425) costs $120 to $150 with breakfast included. At Lawrence’s (38-40 Rua Consiglieri Pedroso, 351-21-910-550; fax 351-21-910-5505) a double room costs between $100 and $180 with breakfast.

Sintra’s Sunday flea market is considered the best on the Lisbon Coast, with an excellent assortment of Portuguese ceramics, rugs, furniture, and antique azulejos. Unfortunately, the crowds from Lisbon make it nearly impossible to move through Sintra on Saturday and Sunday, so visit midweek if you want the city to yourself.

Golf is a popular Portuguese pastime and many of Sintra’s hotels offer packages, with transportation to and from such local courses as Golf do Estoril and Penha Longa. Be sure to ask for extra deals, since golfers are a favored race in the country.

1) The peaceful grounds of the Quinta de Capela have had a calming effect on visitors since the 16th century.

2) Peacocks, a favored pet of Portuguese royalty, still haunt Sintra’s hillsides.

3) The romantic terrace and gardens of the Palacio de Seteais dazzle. The Marquis of Marialva once threw lavish parties here.

4) The breakfast room at the Quinta da Capela is brightly adorned.

5) The 18-century battlements of the Castelo dos Mouros snake across the heights of Sintra’s Sierra mountainside.

6) Glazed ceramic tiles called azulejos adorn sidewalks, public fountains and antique shops throughout Sintra.